The strange case of Nils Lilja & the fuchsia

Monday, July 01, 2024

He later took up botany, geology, chemistry, literature, philosophy and political science on his own. His myriad interests were perhaps hereditary. His father, Hans Nilsson Lilja was also a trained shoemaker, mason and carpenter, as well as an amateur naturalist and successful naturopath, besides being a farmer at Blinkarp.

Seemingly a perennial student due to bad circumstances both financial and physical, Lilja would spend fourteen years at university without ever obtaining the master's degree he was working on. He often solicited the support of friends and admirers, including the crown prince of Sweden Oscar I, who provided scholarships and arranged fundraisers to help finance his continuing efforts.

Among his dozens of publications, the encyclopedic Menniskan: Hennes uppkomst, hennes lif och hennes bestämmelse (Mankind: Its Origins, Life and Destiny; Stockholm, 1858) is perhaps his most significant and enduring effort. It was again a long work in 429 pages covering various aspects of civilization, anthropology and natural history and was intended for a popular audience rather than academia.

The fiery Lilja's multitudinous family lives seemed to be as distracted as his professional interests. He was married three times, fathering fifteen legitimate children. He even found time to father at least four, or perhaps six, additional children off the record with a maid. He seemed to have lost count. Reflecting his interest in botany, Lilja's offspring were sometimes given names inspired by plants.

Lilja's unorthodox views on Christianity and social topics for the times—such as free love and equality of the sexes—of course earned him a certain amount of public and clerical scrutiny but his many friends and supporters remained personally faithful. In recognition of his efforts in the botanical sciences, Lilja was eventually awarded an honorary PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1865. His prodigious extracurricular activities remained unrecognized.

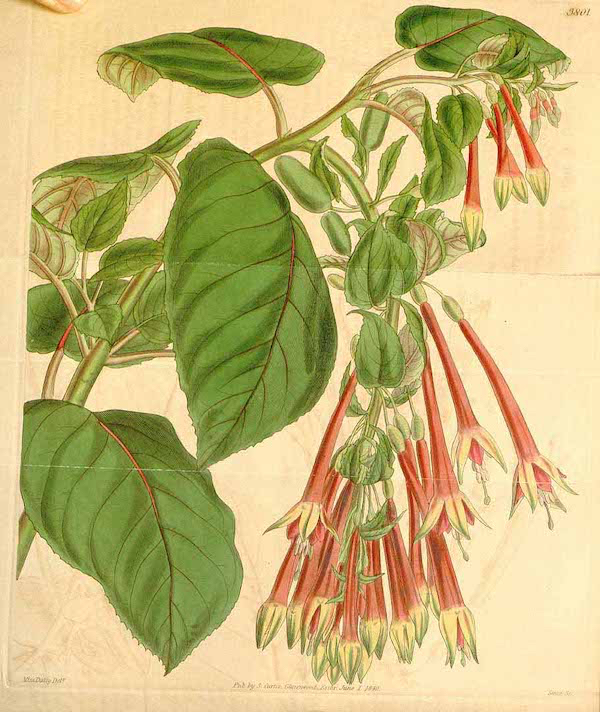

At the beginning of the 1840s Lilja tried his hand at the taxonomy of some Central American fuchsias, quartered in today's Ellobium and Encliandra sections, establishing new genera for two species previously described by Augustin Pyramus de Candolle (1828) and Carl Kunth (1823). These were Spachia fulgens (DC, Lilja 1840), Ellobium fulgens (DC, Lilja 1841) and Myrinia microphylla (Kunth, Lilja 1840). Lilja seemed unsure what to do with Fuchsia fulgens, changing it from Spachia to Ellobium in a year.

The book's full title continues, "innefattande de flesta på fritt land odlade vexter i Sverige, jemte de allmännare och vackrare fenstervexterna…" (including most of the outdoor plants in Sweden, along with the more general and beautiful indoor plants…). His motivation was perhaps the rising fashionableness of fuchsias in the gardens and parlors of Europe.

Lilja's taxonomic efforts on behalf of Fuchsia were eventually overturned and are synonymous with the former names by which they're still known today: Fuchsia fulgens and F. microphylla. He did perhaps manage to leave one mark in his efforts on fuchsias. Ellobium was resurrected for the section of the genus that includes F. fulgens and its two sister species, F. decidua and F. splendens.

Lilja did describe a number of other non-fuchsia species as well. Unfortunately most are of ambiguous legitimacy or have been turned into synonyms. A lucky few, such as Pholistoma aurita Lilja, still stand. Oddly again for this Swedish botanist, Pholistoma is a genus of three flowering plants in the Borage Family native to western North America between Oregon and Baja California and not his native Scania.

Not giving up easily, Lilja published the Fuchsiaceae family in the second edition of his Skånes flora (1870) to house his genera. The family also stays unrecognized. Fuchsia, of course, belongs to the greater Onagraceae, or Evening Primrose Family, and that's where it remains. Not that some of us wouldn't have minded rewarding Fuchsia with a family of its own.

Lilja died in Lund in 1870 at the age of sixty-two, perhaps of exhaustion from his numerous publications and other scattered physical productions. After his death one last successful fund drive was made on his behalf to pay for the granite obelisk raised over his grave in Billinge.

(Illustrations: 1. Portrait of Nils Lilja; 2.Skånes flora (Flora of Scania), 1838; 3. Sveriges odlade vexter, (Flora of Sweden's Cultivated Plants),1839; 4. Fuchsia fulgens, Curtis's Botanical Magazine, Vol. 67, 1841.)