History of the Fuchsia

Yes, there were once fuchsias growing in Antarctica. And Australia, too, while they were at it.

Yes, there were once fuchsias growing in Antarctica. And Australia, too, while they were at it.

The Cenozoic Era

Or the Age of Fuchsias

Or the Age of Fuchsias

PALEOGENE PERIOD

Paleocene Epoch 66–56 ma

Eocene Epoch 56–34 ma

Oligocene Epoch 34–23 ma

NEOGENE PERIOD

Miocene Epoch 23–5.3 ma

Pliocene Epoch 5.3–2.6 ma

QUATERNARY PERIOD

Pleistocene Epoch 2.6 ma–12 ka

Holocene Epoch 12 ka–Today

Paleocene Epoch 66–56 ma

Eocene Epoch 56–34 ma

Oligocene Epoch 34–23 ma

NEOGENE PERIOD

Miocene Epoch 23–5.3 ma

Pliocene Epoch 5.3–2.6 ma

QUATERNARY PERIOD

Pleistocene Epoch 2.6 ma–12 ka

Holocene Epoch 12 ka–Today

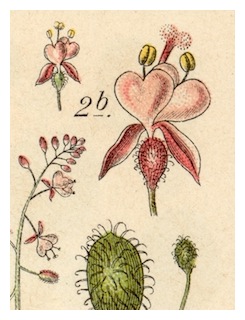

Australia, Antarctica and South America have long been going their own ways after the great break-up of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana. For quite a geological time, though, they seem to have remained somewhat of a trio, these three continents. Australia was still almost connected to Antarctica towards the end of Eocene Epoch (56-34 million years ago) when the dawn fuchsia made its first appearance in the brightening light of an early day. And it wasn’t until the upper half of the Oligocene (34-23 mya) that the Drake Passage even opened enough to meaningfully separate Antarctica from South America. Africa, another former part of Gondwana, had sped off on its own far earlier, but was still just a tad closer to the South Pole in the Oligocene. India was also a bit further to the southwest than it is today and in the earlier stages of crashing into Asia to raise the Himalayas.

That is, until the Drake Passage opened enough during the Oligocene and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current developed about 30 million years ago. [1] Its cold waters now completely surround and isolate the southern polar continent, holding it in an icy embrace. Antarctica probably won’t permanently escape its cold fate as long as this frigid stream cuts off any warmer ocean waters from reaching its shores. [2] By another ten million years, the Andes were also slowly rising high enough, first in the north and then by yet another ten million years in the south, to further affect the world's climate patterns. Antarctic forests slowly gave way to tundra and then tundra to the barrenness of ice.

Or maybe not quite that way either. That tale of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current has been conventional wisdom. However, a very recent paper suggests that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current many not have been the cause of Antarctic glaciation after all, but a symptom of it. Declining levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere might have led to the formation of the continent wide ice sheet, which in turn led to the formation, or at least the strengthening, of the Circumpolar Current. Stay tuned for more on this fascinating direction of research from scientists. In the meantime, back to the Fuchsia. [3]

This new biogeography is an odd one for a proposed southern South American origin. It seems more likely, perhaps, that the genus has moved southwards from a more northerly homeland rather than spreading in the other direction as was originally suggested. From the late Eocene Epoch (56-34 mya) there was a gradual transition from tropical vegetation to temperate forests. Much of the world became covered from pole to pole by these forests in the Oligocene.

Unlike many other members of the Onagraceae that disperse their seeds on tufts carried off by the wind, Fuchsia's tiny seeds are encased in soft berries, The kinds of berries birds like to eat. It’s entirely logical that the earliest Fuchsia was dispersed southwards, most likely by migrating birds, to establish itself along the way into those areas of cooler habitat that were most similar to its original home. In forests at higher elevations, or at cooler lower latitudes. Dispersed right past the bottom of the globe and on to temperate Australia, still much closer to Antarctica on other side of the globe in those days.

Birds, after all, continue to migrate from north to south, or maybe south to north, and back again, as they probably have since they first wore enough feathers to fly any distance.

With other associated genera from the Antarcto-Tertiary Geoflora, Fuchsia was likely spread across land bridges or narrow straights from South America to temperate Antarctica after its origin at the end of the Eocene Epoch into the Oligocene. From there, it went on to Australia, which itself wasn’t fully separated from Antarctica until the opening of the Tasman Sea about 34 million years ago. In fact, fossilized fuchsia pollen grains from the late Oligocene to the early Miocene have been reported from New Zealand and Australia (as well as South America). [5] The fuchsias found in New Zealand today are possibly (re)colonists from Australia. There is some controversial speculation that the whole of the thin and narrow Zealandia continental plate under those islands might have been fully submerged about 23 million years ago, before the land slowly re-emerged. Of course, this theory does't account for the diverse numbers of genera in New Zealand with clear connections to South America and, especially, for fresh-water animals that couldn't easily survive a swim from Australia across salty seas.

At this point, a few skeptics might interject, “But what about the crucial evidence from Antarctica?” Fuchsias are quite hardy plants, after all. But not that hardy to survive Antarctica's demanding weather so... Except for a single badly eroded fossil pollen grain from Seymour Island (1959)—one that may or may not be Fuchsia—there doesn’t seem to much of anything left. Yet. This is not surprising since that continent has been locked under a mile of ice for at least the last 15 million years. Maybe longer. Maybe not. The crucial missing links will eventually be uncovered by scientists on their marks. It makes no sense for Fuchsia to have jumped so far from the proto-Tierra del Fuego to the proto-South Side of Sidney without also spending at least half an epoch or more hanging around the South Pole. There’s no Olympic vaulter of any age capable of that spectacular a leap. There are still a lot of surprises resting deep under Antarctic ice. Those surprises are just kind of hard to get at right now.

The eventual, compete glaciation of Antarctica caused the extinction of any fuchsias on that continent. And the slowly warming, drying climate of Australia, as it drifted ever north towards the hot Equator, accomplished the end of the genus there as well. The remains of distinctive Fuchsia pollen (as Dipordites apsis, now Koninidites apsis) is documented in the fossil record of Australia. It confirms that Fuchsia had once flourished in the temperate forests the land of Oz hosted during the Miocene Epoch. It was likely represented by an unknown number of now-extinct species probably in the Skinnera section. These unfortunately can’t currently be differentiated from the pollen grains.

This hypothesis was recently supported by the description of the fossil-taxon, Fuchsia antiqua, found as an actual fossilized flower, along with a separate associated anther mass, in early Miocene limestone deposits at Foulden Maar in southern New Zealand.

Relatively recently in geological terms, birds most likely spread seed again, as they must have done epochs earlier from North America south. Yet another new species, F. cyrtandroides, is now established in the cooler highlands of the new volcanic island of Tahiti which started forming no more than three million years ago. The ancestor of this Tahitian species, however, split from the rest of the Skinnera section about eight million years ago. There might have been some intermediate island hopping involved in the dispersion as well. Of course, its ultimate ancestor could also have come from Australia by way of New Zealand. Or even more directly from Australia, skipping New Zealand altogether.

According to the recent revealing DNA studies, about 31 million years ago in the Oligocene Epoch, Fuchsia started to diversify into the four major ancestral lineages that are still reflected in the major sections of the genus today.

The Andean lineage, represented by sections Fuchsia and Hemsleyella, seems to have begun differentiating fairly rapidly into a large number of species with the rising of the Northern Andes starting about 22 million years ago. The lineage itself is probably considerably older. The Brazilian members of the southern Quelusia and Kierschlegeria lineages were split away from F. magellanica and F. lycioides by more geological changes caused by the rising Andes in the south as recently as 13 million years ago. In Central America and Mexico, the three sections of Ellobium, Encliandra and Schufia are thought to represent another very early northern lineage. Possibly two. [8]

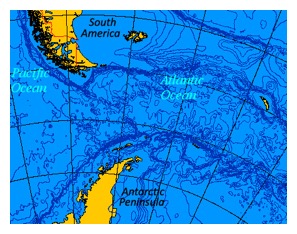

Moving right along into the Holocene Epoch, to the year 1696 to be exact [9], Father Charles Plumier was in the Greater Antilles on his third expedition to the New World....

The Cenozoic Era

Or the Age of Fuchsias

Or the Age of Fuchsias

PALEOGENE PERIOD

Paleocene Epoch 66–56 ma

Eocene Epoch 56–34 ma

Oligocene Epoch 34–23 ma

NEOGENE PERIOD

Miocene Epoch 23–5.3 ma

Pliocene Epoch 5.3–2.6 ma

QUATERNARY PERIOD

Pleistocene Epoch 2.6 ma–12 ka

Holocene Epoch 12 ka–Today

Paleocene Epoch 66–56 ma

Eocene Epoch 56–34 ma

Oligocene Epoch 34–23 ma

NEOGENE PERIOD

Miocene Epoch 23–5.3 ma

Pliocene Epoch 5.3–2.6 ma

QUATERNARY PERIOD

Pleistocene Epoch 2.6 ma–12 ka

Holocene Epoch 12 ka–Today

TO BE CONTINUED

Illustrations: 1. A penguin in Antarctica; 2. Two Caribbean natives. Drawn by Charles Plumier on one of his botanizing expeditions to Hispaniola, where he also described the first fuchsia, Fuchsia triphylla; 3. Now 1000 km wide, the Drake Passage separates South America and Antarctica. Seymour island is at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.; 4. Circaea; 5. Hauya; 6. Berries of Fuchsia paniculata, native to Mexico and Central America; 7. Wollemi nobilis; 8. Fuchsia antiqua; 9. Fuchsia magellanica and a DNA strand; 10. Fuchsia magellanica along the shore of Lago Moscardi in the Patagonia Lake District, Argentina.

[2] There are indications that the ice sheet has retreated significantly in the past. In 1985, the remains of a 3-million-year-old temperate forest that stretched for about 1,300 kilometers along the Transantarctic Mountains were discovered. Unfortunately, there doesn’t also seem to be any indication that fuchsias re-introduced themselves along with the trees. ➤ More. ➤ Return to reading.

[6] Sand Grains and Fossilized Pollen Reveal Climate History of Northern Antarctica. ➤ Article. ➤ Return to reading.

[7] Daphne E. Lee, John G. Conran, Jennifer M. Bannister, Uwe Kaulfuss and Dallas C. Mildenhall. A fossil Fuchsia (Onagraceae) flower and an anther mass with in situ pollen from the early Miocene of New Zealand, American Journal of Botany, October 2013, 100:2052-2065; published ahead of print 8 October 2013. ➤ Article. ➤ Return to reading.

[8] A good chart of the relationships within the genus and its close relatives can be found here. ➤ Chart. ➤ Return to reading.

[9] It’s a refreshing change, actually, to be able to be so precise. Scientists can be maddeningly imprecise, for all the millimeters and microns and eons. Getting the dates of the epochs to agree has been a chore. Did the Eocene end 34 million years ago? Or 38? It’s almost like a poker game. One scientist will say 34 million. Another will come along and say, “I match that and raise you 4 million.” In the end, I settled on what I hope are the latest thoughts on the subject. Precisely assigned dates, though, don’t seem to matter that much in geologic time. It’s more about the general look and feel of big chunks of it, where one chunk blends ever so slowly into the other, rather than about clean slices and precise fixes. After all, what’s really a million years or two, or maybe even three, in the great slow flow of the hundreds of millions of years of our Earth’s geology? At five, let’s talk. That’s it. Now back to Plumier... ➤ Return to reading.