The Lady with the Fuchsia Corsage

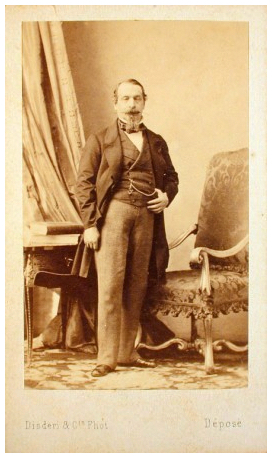

The portrait-carte, sometimes portrait carte-de-visite but usually known inaccurately in English as just a carte-de-visite, was a type of photographic visiting card patented in 1854 by the Parisian photographer, Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889). Based on the indispensable visiting cards of the Victorian Age, these thin albumen silver prints were approximately five by nine centimeters in size, mounted on slightly larger pieces of cardboard of about six by ten centimeters.

The portrait-carte was initially slow to catch on with customers due to the high cost of the individual prints. Disdéri later invented a more economical process to produce eight prints at a time. With the publication of a portrait of French Emperor Napoléon III in 1859, the portrait-carte suddenly became quite fashionable. Its use took off like wildfire spreading out from Paris to the rest of world for everyone anywhere who wanted to be anyone stylish.

After 1880, the smaller portrait-carte was replaced by the larger cabinet card, variously called in French a format cabinet, carte cabinet, photo-carte format cabinet, or a portrait format cabinet. Still mounted on board. the dimensions of the cabinet card were about eleven by almost seventeen centimeters. Even larger cards, usually of notable people, were produced that measured thirty-five by fifty centimeters.

The cabinet card generally included a wider border at the bottom of the mounting that identified the photographer and his particulars. The style of the card on which the print was placed changed over the years and that can be used to roughly date a portrait or image. Unfortunately, while most sitters were known to owners, they're mostly anonymous to us today as they by-and-large lack any kind of identification of the subject on the back. Except again often repeating the photographer or studio there.

Eventually, cabinet cards faded from fashion and then slipped into oblivion. Their use diminished through the 1920s and by 1930, they were gone. World War I might have had a large hand in upsetting the comfortable expectations and assumptions of lives lived during the Belle Époque. The advent of the affordable Kodak Box Brownie in 1900 was probably the bigger factor in the eventual disappearance of the cabinet card, though. Much like digital images versus film today, quick and easy personal photography became affordable to many people and helped supplant the more formal cabinet card.

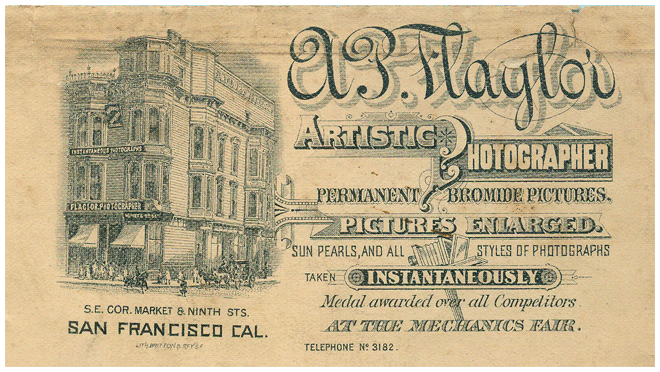

I have a cabinet card with the portrait of a lady, seemingly in her late twenties or early thirties. Or younger maybe. Her identity is unknown as is often the case with these cards, The photographer's name, though, is in fancy cursive gold lettering at the wider bottom of the black border. It's faded a bit but the name "Flaglor" can be made out on the left. "Instantaneous Photographs" appears on the right side. There's a wide space between "S.E" and "Market & Ninth Sts" printed in smaller letters below that. The wide space was probably filled with the now almost fully faded abbreviation "Cor." for Corner. "San Francisco" is found in even smaller lettering in the lower right corner. The back is blank. The style of the image and its mounting suggest the card dates to the 1880s.

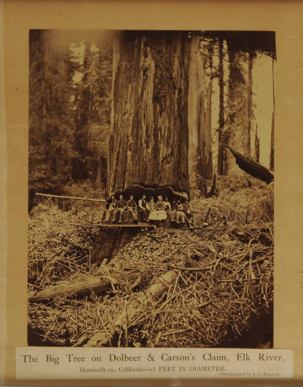

While the identity of the sitter may not be known, the identity of the photographer, fully Amasa Plummer Flaglor, is certainly known. Well known, in fact. A.P. Flaglor had a quite successful career. Born to American parents in New Brunswick, Canada in 1848, he moved with his mother to San Francisco at the age of 14 where he apprenticed in a photo studio. Flaglor eventually worked for several studios, even opening and closing his own several times in San Francisco.

Probably drawing on his own early experience, Flaglor firmly believed in the value of apprenticeships to train photographers and many of his own apprentices would go on to become outstanding photographers of Northern California themselves.

Financial difficulties, though, eventually forced a return to San Francisco with his wife and family. Working at first for another photographer, Flaglor was able to open a studio of his own again after saving enough money to do so. The portrait of the lady in my cabinet card was certainly done during this period. He operated what was to be his last photography business until 1893 when he oddly and completely changed careers to become an investment broker and insurance agent. Flaglor died in 1918.

I'd suspect the anonymous lady put together the corsage from her own garden that morning just for the sitting. Fuchsias were considered quite fashionable plants during the Nineteenth Century. Very much so. Potted fuchsias were even known to have been carefully carried in wagons westward across the continent by homesteading women just a decade or two earlier. Then they started arriving in West Coast ports carried by trade ships traveling around Cape Horn. Not an inexpensive passage for garden plants at all.

It's not out of line to think the fuchsia adornment speaks out with a touch of pride of both fuchsia ownership and cultivation, as well as an intended dash of Victorian chic, in an increasingly sophisticated city. And it probably elicited a bit of envy from the contemporary viewer, too. Perhaps one day I'll be able to discover the identity of the fashionable Lady with the Fuchsia Corsage herself. Who knows?

(Illustrations: 1. Couple in a typical Victorian parlor, Roxbury, Massachusetts, ca. 1880. 2. Portrait-carte of Napoléon III, Eugène Disdéri, 1859. 3. Yale Bulldogs, 1895. 4. Advertisement for A. P. Flaglor's studio in San Francisco. 5. The Big Tree on Dolbeer & Carson's Claim, Elk River, Humboldt Co. California. A.P. Flaglor, 1872. 6. Detail of the fuchsia corsage on the Lady with a Fuchsia Corsage. 7. Full cabinet card of a Lady with a Fuchsia Corsage, A.P. Fraglor, San Francisco, 1880s.)