Happy Lantern Festival

Fireworks! The Chinese New Year certainly comes in with some big bangs and more than a few snap, crackle and pops. But it’s the Chinese Lantern Festival that marks the last day of traditional Chinese New Year celebrations. Its bright lanterns symbolize the letting go of past selves and the acquisition of new ones in the coming year, and they are usually bright, exuberant red for good fortune and good measure. This ancient festival falls on the fifteenth day of the first month of the lunisolar Chinese calendar. In 2017 that means February 11 on the Gregorian Calendar.

Today paper lanterns are often embellished with complex designs. A popular activity is to solve the riddles and puzzles written on the lanterns, which might contain messages of good fortune, harvest, and family reunion.

A glutinous rice ball cooked in soup is also typically eaten during the festival. It might seem a lot to ask of a glutinous rice ball, but the round shape, and the bowls in which it’s served, symbolize familial togetherness, and the hope for happiness and good luck in the coming new year.

Known as early as the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-25 AD), the Lantern Festival quickly became a celebration with great cultural significance. Emperor Wudi already attached special importance to the festivities and in 104 BC decreed that they should last the whole night through.

There are a number of theories about how the festival came to be. The most likely

Not content with anything that simple, a number of colorful legends developed about the origins of the celebration. One tells that this was a time to worship Taiyi, the God of Heaven, who controlled the destiny of the world. Taiyi had sixteen dragons at his service and he would often arbitrarily send them out to inflict great harm and troubles on human beings through drought, storms, famine, or pestilence. Ouch.

Beginning with Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, splendid ceremonies were held each year and China’s rulers would beg the perennially petulant Taiyi to bring favorable weather and good health to their lands instead of pain and misfortune.

Other legends and stories connect the festival to the Daoist God of Good Fortune, Tianguan; atonement for the killing of a crane sent by the Jade Emperor of Heaven; or link it to the shenanigans of Dongfang, the God of Fire. Take your pick.

As time passed festivities became ever more elaborate. By the beginning of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) the lantern display would last for three days. Curfews were lifted so that even the depressed common people might celebrate day and night. Poets composed poems that extolled the revelry.

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the festival now extended for five days. Lanterns might be made of colorful glass, or even precious jade, and painted with figures from folk tales. The common folk probably kept to the traditional paper.

Lantern Festival celebrations reportedly reached their peak by the early part of the fifteenth century during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) by which time festivities went on for ten days. The Emperor Chengzu (b. 1360; reigned 1402-1424) had all of downtown Beijing hung with lanterns.

For contemporary displays, much as Christmas lights in the West have gone from candle power to electric, Hangzhou and Shanghai have modern electric and neon lanterns alongside traditional paper or wooden ones.

Coincidentally for the date, the Lantern Festival had an odd bit of Valentine’s Day to it as well. Marriageable young people would be chaperoned around the streets in the hope of finding true love. Matchmakers were kept busy pairing possible couples.

The bright lanterns symbolized their dreams and expectations. Young ladies might also write their names and other pertinent contact info on mandarin oranges and expectantly toss them into the stream in the hopes that they’d be plucked out by the right guy. Proto-texting via citrus fruit, it seems.

These amorous traditions have faded away in parts of modern China but the Lantern Festival is still celebrated as a kind of Valentine's Day by the Chinese of Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Oh, and finally, one of the two common names for the fuchsia in Chinese is 吊 灯 花 (Diàodēnghuā). The hanging lantern flower. So Happy Lantern Festival everyone. Hang those hanging lanterns high. May your new selves be happy, healthy and prosperous. And fulfilled with fuchsias. Lots of them.

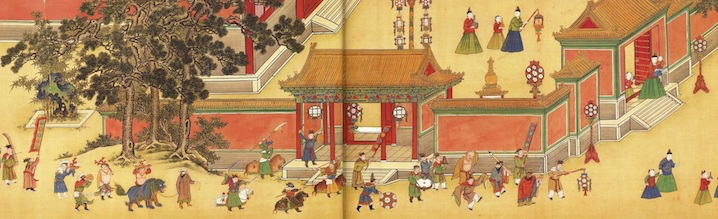

(Illustrations: Ming-dynasty Emperor Xianzong enjoying festivities with families in the Forbidden City during the Lantern Festival with acrobatics, operas, magic shows and firecrackers in 1485.)