Happy birthday, Leonhart Fuchs

Fuchsia triphylla, flore coccineo. Leonartus Fuchsius Vembdingæ, Rhætiæ Oppido in ditione Ducum Bavariæ natus 1501. Medicinæ Doctor renunciatus Monachum aditt, deinde Tubingum, ubi 35. annis præclare docuit. Vir fuit assidui laboris, plantarum Germaniæ diligens explorator. Magno herbariorum commodo harum icones 510. amplioris formæ exhibuit. Tubingæ mortuus est anno 1566. 10. Maji, ætatis 65. Scriptsit de Historia stirpium commentarios insignes: Basileæ 1542. in folio.

Charles Plumier

Novum Plantarum Americanorum

1703.

My, how time flies. That eminent botanist, Leonhart Fuchs, turns five hundred and thirteen today. He was, in case you’ve been distracted the whole time, the German physician, botanist and professor after whom Father Charles Plumier had baptized the Fuchsia, a marvelous new genus he had discovered growing on the island of Hispaniola in 1695/96. Euphony aside, one wishes that more could be said about Fuchs regarding the plant named in his honor. But the reality is that the honor is actually more or less arbitrary. And very posthumous. Sadly, the eminent Doctor Fuchs never met his Fuchsia, having died almost a hundred and fifty years earlier. Still, he was a true man of the Renaissance who certainly deserved to be recognized botanically, even if the honor was a tad long in coming.

Leonhart Fuchs was born in 1501 in the town of Wemding, then part of the Imperial County of Oettingen in the Holy Roman Empire. Today it’s a small municipality in the Donau-Ries district of Bavaria. After early studies at the University of Erfurt, started when he was a precocious fourteen, he moved to the University of Ingolstadt to first study the classics, then shortly take a degree as a doctor of medicine for good measure.

His reputation spread broadly and was soon apparently such that Duke Ulrich of Württemberg (1487-1550), called on him to help with his reforms to infuse the University of Tübingen with the spirit of humanism. The ambitious Fuchs arrived in 1535 and would remain at the prestigious university, where he taught and held the chair of medicine, until his death there in 1566. He would serve as its chancellor seven times.

It’s not unsurprising that such an accomplished Renaissance man of medicine and other matters was heavily influenced by the renewed interest in the classical texts of ancient Greece and Rome. Where Fuchs shone in his own age, however, was in his emphasis on practical experience and hands-on training.

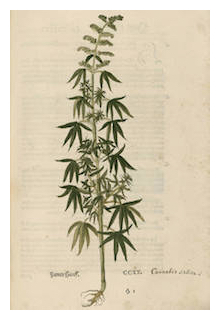

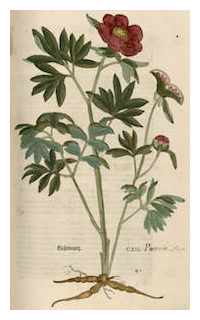

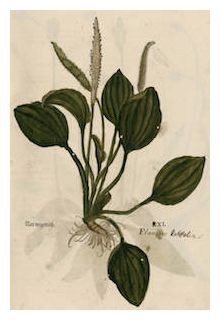

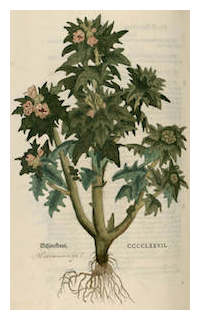

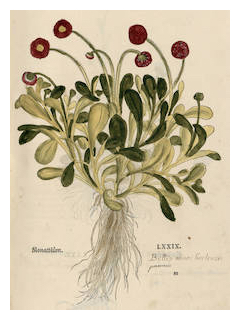

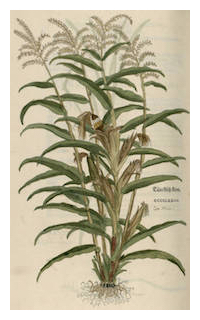

As a teacher, Fuchs was ground-breaking. However, his magnum opus and the major source of his enduring fame would be De historia stirpium commentarii insignes—Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants—a huge herbal published in 1542. Almost a decade in the making, this great work was again ground-breaking. It contained over five hundred exceptionally well-executed woodcuts of medicinal plants and herbs taken from his garden and nature. The ever-practical Fuchs usefully attempted to matched them to Dioscorides’s ancient medical text.

Fuchs tried to methodically match a classical medical text to actual plants that he knew and grew. It's interesting to speculate, however, just how aware he was of the amazing botanical riches rapidly approaching on the western horizon from the New World. Among the exotics and novelties, he did recognize chili peppers in his herbal, adding a new bit of spice to contemporary medicine. And Zea mays. But sadly he didn't get his information completely in order on that one. As Turkish Corn, he placed it as a native of clichéedly exotic Turkey rather than the Americas. Then again, the newly introduced Turkey Fowl also suffered from the same contemporary misconception of the East as the source of all things mysterious, or it might have been called the Mexico Fowl instead.

(Illustrations: From Leonhart Fuchs’s De historia stirpium, Basel, 1542. 1. Detail from Fuchs’s portrait; 2. Capsicum annum; 3. Borago officials; 4. Cannabis sativa. He was a doctor, after all; 5. Full length portrait of Fuchs; 6. Byronia alba; 7. Paeonia officinalis; 8. Plantago major; 9. Hyoschyamos niger; 10. Bellis perennis; 11. Zea mays; 12. Allium shoenopranum.)

Share this entry on Twitter

Tweet