The ginkgo. There's an orchard hidden on my block

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Out front, on the street, the ginkgo leaves have finally fallen. They turned bright saffron-yellow and gold over the last week or two. Then suddenly, and seemingly all at once, they fell together with an intent that must have been choreographed from tree to tree. For the longest time the ginkgo trees had remained stubbornly green, with their secret hidden within the dense cover of their elegant fan-shaped leaves. When this then-novel species first arrived on the scene from the Far East in the eighteenth century, it was somewhere dubbed the maidenhair tree, not from any chaste sense of modesty but because its leaves seemed like the familiar fronds of some maidenhair ferns. But Lineaus and Science accepted it as Ginkgo biloba in 1771.

intent that must have been choreographed from tree to tree. For the longest time the ginkgo trees had remained stubbornly green, with their secret hidden within the dense cover of their elegant fan-shaped leaves. When this then-novel species first arrived on the scene from the Far East in the eighteenth century, it was somewhere dubbed the maidenhair tree, not from any chaste sense of modesty but because its leaves seemed like the familiar fronds of some maidenhair ferns. But Lineaus and Science accepted it as Ginkgo biloba in 1771.  Most people now know it that way, as well, despite numerous references and plant labels that helpfully insist, “also known as the Maidenhair Tree. No. Not really. Not commonly. Not by anyone I know. It’s always the ginkgo. Except to the pundits who write references, I suppose. The genus epithet itself is a garbling of the Japanese rendering of the old Chinese name 銀果 (pronounced yínguǒ in modern Mandarin), or the silver fruit, that accompanied the ginkgo on its early spread out of its native China alongside Buddhism.

Most people now know it that way, as well, despite numerous references and plant labels that helpfully insist, “also known as the Maidenhair Tree. No. Not really. Not commonly. Not by anyone I know. It’s always the ginkgo. Except to the pundits who write references, I suppose. The genus epithet itself is a garbling of the Japanese rendering of the old Chinese name 銀果 (pronounced yínguǒ in modern Mandarin), or the silver fruit, that accompanied the ginkgo on its early spread out of its native China alongside Buddhism.

urbanite of any age taking this kind of interest in the urban landscape that I was immediately curious to see what she was seeing. The ginkgo has become widely planted along the streets in the City because it’s such elegant, resilient tree, growing straight between the increasing urban heights being developed to either side, rather than bending out in search of light, tolerant of air pollution and the restrictions of sidewalk tree wells. It’s the last of its kind, Ginkgo biloba, a living fossil. The rest

urbanite of any age taking this kind of interest in the urban landscape that I was immediately curious to see what she was seeing. The ginkgo has become widely planted along the streets in the City because it’s such elegant, resilient tree, growing straight between the increasing urban heights being developed to either side, rather than bending out in search of light, tolerant of air pollution and the restrictions of sidewalk tree wells. It’s the last of its kind, Ginkgo biloba, a living fossil. The rest  of its relatives flourished so long ago that dinosaurs snacked on them for lunch. It’s sad because this last ginkgo is actually a very hardy, exceptionally long-lived tree, the oldest thought to be fifteen hundred years of age. Or more. Judging from the fossil leaves and similar habitats recorded in the stone, the diversity of its kindred would have been amazing. Oh, well. She caught me looking into the tree as well and expressed a twinkling, knowing smile that spoke of some secret only she and I shared. But I was off to work and left the moment behind. And Grandmother moved on to another tree as I glanced over my shoulder.

of its relatives flourished so long ago that dinosaurs snacked on them for lunch. It’s sad because this last ginkgo is actually a very hardy, exceptionally long-lived tree, the oldest thought to be fifteen hundred years of age. Or more. Judging from the fossil leaves and similar habitats recorded in the stone, the diversity of its kindred would have been amazing. Oh, well. She caught me looking into the tree as well and expressed a twinkling, knowing smile that spoke of some secret only she and I shared. But I was off to work and left the moment behind. And Grandmother moved on to another tree as I glanced over my shoulder.

It wasn’t until later, on my way home, that it came to me just what secret had passed between us in her happy eyes. The ginkgo is dioecious. The male trees bear pollen cones and the female bear the fruit. The fleshy outer layer of that fruit, the sarcotesta, presents one major problem for a sidewalk tree after it falls, though. It’s full of butyric acid and the very malodorous smell that develops on the ground is variously

It wasn’t until later, on my way home, that it came to me just what secret had passed between us in her happy eyes. The ginkgo is dioecious. The male trees bear pollen cones and the female bear the fruit. The fleshy outer layer of that fruit, the sarcotesta, presents one major problem for a sidewalk tree after it falls, though. It’s full of butyric acid and the very malodorous smell that develops on the ground is variously described as rancid butter or vomit. Or worse. Male trees are often planted to avoid the problem but they are more expensive, being grafted to ensure the sex. Many of the trees along my street were simply grown from seed so naturally there’s a proportion of female trees. And there are several in the bunch. Their fruit has been a source of much amusement over the years as I watch clueless pedestrians often stop to inspect the soles of the shoes, assuming the worse, as they pass by. Doormen and supers quickly put an end to the fun when they regularly wash the sidewalk out into the street. Some not so quickly as the others, though, it seems.

described as rancid butter or vomit. Or worse. Male trees are often planted to avoid the problem but they are more expensive, being grafted to ensure the sex. Many of the trees along my street were simply grown from seed so naturally there’s a proportion of female trees. And there are several in the bunch. Their fruit has been a source of much amusement over the years as I watch clueless pedestrians often stop to inspect the soles of the shoes, assuming the worse, as they pass by. Doormen and supers quickly put an end to the fun when they regularly wash the sidewalk out into the street. Some not so quickly as the others, though, it seems.

Get past the smelly pulp, however, under a hard shell, called the sclerotesta by botanists, is an edible nut-like seed that’s been prized in the cooking of various Asian countries, from Thailand to Japan, for centuries. The secret that had passed so knowingly between us, even though it took me a while to know I knew, was the urban orchard of ginkgo right under everyone’s noses. Grandmother was taking a census of the fruiting trees and would certainly be back to claim the precious prizes. In fact, I often encountered her over the next few years, mostly at harvest time collecting the bounty from her orchard. Not this year or the last, sadly, and no one seems to have taken her place. But still I give the trees a knowing smile, just the same, as I pass by them every morning this bountiful time of year.

Get past the smelly pulp, however, under a hard shell, called the sclerotesta by botanists, is an edible nut-like seed that’s been prized in the cooking of various Asian countries, from Thailand to Japan, for centuries. The secret that had passed so knowingly between us, even though it took me a while to know I knew, was the urban orchard of ginkgo right under everyone’s noses. Grandmother was taking a census of the fruiting trees and would certainly be back to claim the precious prizes. In fact, I often encountered her over the next few years, mostly at harvest time collecting the bounty from her orchard. Not this year or the last, sadly, and no one seems to have taken her place. But still I give the trees a knowing smile, just the same, as I pass by them every morning this bountiful time of year.

P.S. The oldest Ginkgo biloba in North America is growing at Bartram’s Garden on the Schuykill River, just south of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dating to 1728, Bartram’s Garden is also the oldest botanical garden in the United States. Seeds of the tree came here by way of London to William Hamilton, who owned a neighboring estate called the Woodlands. Hamilton established two trees for himself and gave this male tree to William Bartram in 1795. Unfortunately, neither the Woodlands nor its two even older ginkgo trees have survived the ravages of urban development. ➤ Bartram’s Garden Blog. ➤ Bartram’s Garden Website.

P.S. The oldest Ginkgo biloba in North America is growing at Bartram’s Garden on the Schuykill River, just south of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dating to 1728, Bartram’s Garden is also the oldest botanical garden in the United States. Seeds of the tree came here by way of London to William Hamilton, who owned a neighboring estate called the Woodlands. Hamilton established two trees for himself and gave this male tree to William Bartram in 1795. Unfortunately, neither the Woodlands nor its two even older ginkgo trees have survived the ravages of urban development. ➤ Bartram’s Garden Blog. ➤ Bartram’s Garden Website.

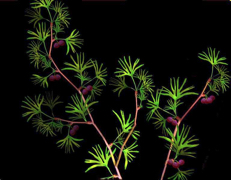

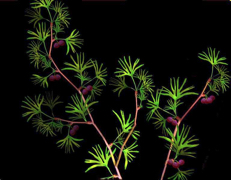

Ginkgo biloba’s fall leaves and smelly fruit.

I first saw her a few years ago, the Chinese Grandmother, standing under one of the ginkgo trees planted along my block. I’d never noticed her before but there she was standing in the early morning sun, still and peering intently into the overlapping foliage high overhead. It’s so rare to find a fellow

Share this entry on Twitter

Tweet

➤ Return to Blog Index