The fuchsia spotlight. Venus Victrix

Finicky, yes. Yet Fuchsia ‘Venus Victrix’, true to its classical name, is a classic. Many better, even prettier, contemporaries faded off numerous decades ago but this particular Diva has remained exceptional for the one very significant quality that made it the celebrated star of screen and stage in the first place. ‘Venus Victrix’ was the first fuchsia in cultivation with a white calyx.

Beyond that quirk of beauty, and in spite of its misbehavior and temperamental disposition, it often imparted that white calyx to descendants that were much, much better. ‘Venus Victrix’ was the color breakthrough that made many later, better crosses with beautiful white or pale-colored calyces possible. Some early offspring which have since disappeared from view included ‘Lady Franklin Smith’ (Smith 1853), ‘Thalia’ (Turner 1855) and ‘Venus de Medici (Banks 1856). James Lye, famous for his own fleshy, cream-pale calyxes, would have been much the poorer for his efforts without the smooth influence of ‘Venus Victrix’ in his body of work. And ‘Venus Victrix’ continues to please. The all-around excellent and very hardy all-white ‘Hawkshead’ was bred in 1962 from a cross with Fuchsia magellanica ‘Alba’.

Not just the inheritor of this large country seat from her father, the Reverend James Marriott, his daughter Elizabeth Marriott Smith (1770-1847) was also an heraldic heiress. Her second son, the equally Reverend William Marriott Smith, later took his mother’s family name and arms in addition to his father’s by royal warrant. The Rev. Sir William Marriott Smith-Marriott would also became the 4th Baronet Smith for a couple of years when his heirless elder brother, the 3rd Baronet, predeceased him in 1862. He had moved to Rectory Park, where he became rector of the parish of Horsmonden as his grandfather had been before him, in 1825.

Interestingly the village of Horsmonden was also the ancestral home of the Austen family at Chapel Manor, local gentry who had elevated themselves socially from their great success as wool merchants. The family’s most celebrated member was the novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817). She set her works of romantic fiction among the landed gentry such as the Smith-Marriotts, whom she certainly would have known. Both the Revs. Marriott and Smith-Marriott (from 1825-1864) were rectors of Horsmonden parish and several members of the Austen family lie buried in the graveyard of St. Margaret’s Church. Jane’s own father, the Reverend George Austen (1731–1805) was the parish rector of Steventon, Hampshire, where she was born. Her grandfather continued to live at Horsmonden. In 1887 Sir William Bosworth Smith-Marriott (1865-1943), 8th Baronet and grandson of the Rev. William, would marry one of Jane’s Horsmonden relatives, Charlotte Marianne Austen (1857-1910).

Jane Austen herself died too early at forty-one to be fully aware of the great fashion for fuchsias that would increasingly take hold at country estates such as Rectory Park in the decades following her death. A beautiful pair of double trailing fuchsias, however, grace the entrance of a stone cottage in the film adaption of one of her novels. ’Swingtime’ is a beautiful cultivar, with its large fluffy flowers of red and white, but it does look a little uncomfortable having a cameo in a Jane Austen film. It was only bred in California by Horace Tiret in 1950.

Such significant discoveries usually travel from the discoverer at the speed of sound. Which seems evident from the short time between discovery and sale in this case. The Rev. Smith-Marriott himself, who only became the rector of the parish in 1825, definitively concludes any argument by actually having had the foresight to mention the birth of ‘Venus Victrix’ in his diary. According to Anthony Cronk, in about 1840, Smith-Marriott wrote of a “moment of ephemeral fame among horticulturalists when Mr. Gulliver, his gardener, raised the first fuchsia with white sepals which he [Smith-Marriott] named ‘Venus Victrix”. 1840. 1841. 1842. Settled.

I sometimes wonder if Smith-Marriott might not have been somewhat influenced in his choice of name by the fact that Queen Victoria, who was also relatively short and upright, had only recently ascended the throne in 1837. Victoria’s father was the Duke of Kent as well. Nominally at least. The Reverend Smith-Marriott was the rector of a small country parish and comparing the white calyx of this new fuchsia to the white skin of the Goddess of Love seems a little less modest that one might expect from a man in such a position in 1840. Oh, well. The Victorian Age wasn’t in full swing yet and previous queens had often been compared to goddesses, such as Elizabeth to Diana. Or Mary to Hecate. Just kidding on that last one.

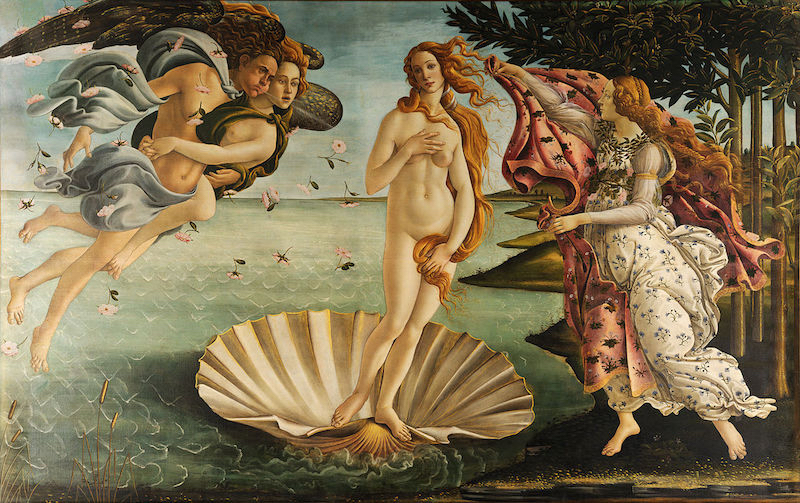

‘Venus Victrix’ does have visual attraction, romantic name recognition, and commercial appeal. Classical allusions abound in art and literature. Even in gardens. And even from rectors. He was an educated man after all. I’m sure he was imaging the classical cold white marbles of ancient Greece and Rome and thought the sepals looked a bit like the missing arms of the Venus de Milo. Smith-Marriott was also the lord of the manor of Horsmonden so he had other responsibilities besides his rectoring like naming flowers.

“The flowers of this unique variety are white, sepals delicately tipped with green, with a superb bright purple corolla, the stamens of a delicate rose, and the pistils white. The plant is of excellent habit, with foliage about the size of F. gracilis, of which it is believed to be an accidental variety.” He created quite a stir. As a writer for British Gardening reminisced even a half-century later, “It was Thomas Cripps who startled the fuchsia-loving world by the announcement of his Venus Victrix”. Reminders enticed weekly until the plants were ready for delivery in May. London? No problem. Orders would be taken through his agents there.

While Cripps wasn’t responsible for breeding the first white fuchsia which look the gardening world by storm, the nursery would achieve more lasting fame with another genus, Clematis. The list of releases that originated there is fairly long. A number of cultivars are still very popular and include widely available hybrids such as ‘Jackmannii Superba’, Lady Caroline Nevill’ and ‘Star of India’. The nursery, which would later become Cripps & Son, was also recognized for its trade in trees, such as maples and conifers.

At that rate, even if Cripps sold only fifteen plants, he would at the very least have covered the money he’d invested in the acquisition. He probably far exceeded that number considering the excitement the appearance this novel pale fuchsia caused. And the genteel, moneyed clientele and their estate gardeners would certainly not have hesitated to meet his price. It’s almost a given that he laughed his way to bank that year. Venus the Victorious, indeed.

Aside from statements that Gulliver raised the first white-sepalled fuchsia, the precise details of ‘Venus Victrix’s generation have remained a bit of a mystery. Some writers ascribe its arrival to a seedling, the most usual way in which most new cultivars are developed. Others call it a sport. That might have been a possibility. Gulliver could have discovered ‘Venus Victrix’ as a changed shoot or branch to be rooted and grown on. Such mutations aren’t uncommon on fuchsias and have provided a good number of named plants. However both seem guesses. Or maybe both could be right and a seedling itself sported in sprouting.

The 1842 advertisement accompanying the introduction of ‘Venus Victrix’ has an interesting statement: “foliage about the size of F. gracilis, of which it is believed to be an accidental variety”. The vague wording might be taken to indicate that Cripps, Gulliver or both felt it has somehow sprung from “F. gracilis”—the cultivar is today rendered as F. magellanica ‘Gracilis’ since it’s not an actual species—but were still unsure of the exact parentage. Not unsurprising if it wasn’t an intentional cross.

In 1875, a correspondent reports in the same Gardiner’s Chronicle where Cripps had first advertised the coming availability of ‘Venus Victrix’, “Mr. Hemsley may like to learn the origin of the first white Fuchsias—Venus Victrix. It was a chance seedling raised thirty-five or forty years ago at Horsmonden Park, in Kent. The gardener, Mr Gulliver, seeing a ripe berry on one of his pots, smeared it with his thumb on the surface of the mould. In the following spring several seedling plants appeared, which were potted off, and one of these proved to be this very elegant and novel variety. It was sold to Mr. Cripps for £15. I had these particulars from Mr. Gulliver himself. S. S.”

Granted there are a few intervening decades between germination and report, and time does tend to shift remembrances, but the report is less hearsay than heard say. Given the recollections and triangulation, though, ’Gracilis’ was likely the source of the berry squashed by Gulliver into the mould.

Most of what today pass as F. magellanica, of one kind or another, are in reality hybrids of slightly varying percentages with F. coccinea. F. coccinea was really the first fuchsia known to be in general cultivation in England and it was so usually confused with the similar-looking F. magellanica, which arrived on the scene at almost the same time, that it’s impossible to tell which is meant to be which in early references.

F. magellanica is generally much more robust over winters in the British Isles and elsewhere than F. coccinea, having evolved in the relatively harsh climate of the southern tip of South America. F. coccinea knows some frost and freeze in the mountains of its origin but it’s a Brazilian species, after all, so what does it really know about the raw and frigid climatic conditions of the Straights of Magellan? It was mostly confined to the stoved greenhouse back then. Global warming has since allowed it to play about the open garden more.

Like little cupids, bees make busy as they always do and berries dropped from plants summering in the open air probably soon gave rise to outdoor garden populations of diluted but mostly F. magellanica parentage. Weaker crosses died out in the winter as the stronger took over. Others continued to spend their winters under glass. Some were selected and propagated. F. magellanica ‘Gracilis’, the supposed parent of ‘Venus Victrix’, is one such plant. F. magellanica hybrids have also thrown a number of vegetative sports over the years, especially in leaf color. Some common examples are ‘Aurea’, ‘Variegata’, and ’Tricolor’.

(Illustrations: 1. & 8. Venus Victrix, Floricultural Cabinet, 1853, vol. 10, p. 169; 2. Rectory Park, Horsmenden; 3. Venus de Milo; 4. The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, about 1485–1486; 5. Queen Victoria, Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1843; 6. Horsmonden Station; 7. George III guinea of 1813.)