Further heraldry of the fuchsia. Dreams of royal realms

For the only other heraldic fuchsia that I know of, you have to go to an island much further afloat than Man. Very much further. Afloat in the South Pacific, in fact. But there, as in Flowers and Heraldry, the heraldic fuchsia is again more fanciful than real. As is the curious adventure of its arrival on this shield.

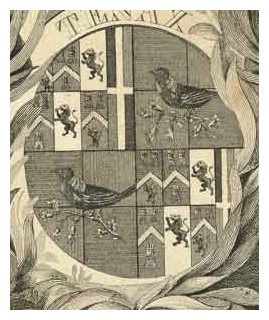

Not unsurprisingly, a tui-bird sits on a flowering branch of the kotukutuku, Fuchsia excorticata, the native tree fuchsia of New Zealand, in the second and third quarters of a fantastical coat of arms assumed by the chimerical and wacky Anglo-French adventurer, “Baron” Charles Philippe Hippolyte de Thierry (1793-1864).

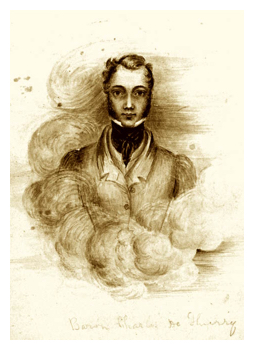

Charles Philippe de Thierry was apparently born somewhere on the road, perhaps Grave in the Netherlands, or even in England already by other accounts,

The elder Thierry’s self-enhancement seems to have worked out quite well for his family, though, even if they were generally strapped for cash. In 1796, during a visit to Edinburgh, little Charles Jr. became a godson of the exiled Comte d'Artois, who would later ascend the French throne as Charles X. In 1814, Thierry tagged along with the Portuguese delegation to the Congress of Vienna, where he was applauded for his violin playing, and served briefly as an attaché at the French embassy in London in 1816. By 1819, he eloped and married Miss Emily Rudge, the daughter of an Anglican archdeacon in whose household he was living and teaching piano. They would have four sons and a daughter.

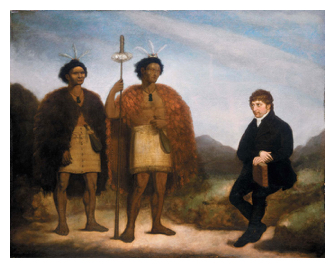

Educated at Magdalen College, Oxford, and later possibly attending Cambridge if his assertions are actually true, the younger Thierry seems to have continued the great family tradition of creative social advancement. As well as the tradition of suffering from strained circumstances. In 1820, he supposedly purchased 40,000 acres for a colony in the Hokianga in New Zealand in some sort of arms-for-land deal—for thirty-six axes, on account—from a couple of Maori chiefs visiting Cambridge with the colorful missionary, Thomas Kendall.

For the next decade, Thierry approached the British, Dutch and then the French governments with his so-called deed in support of lofty schemes to establish the colony, with himself generously serving as governor or some sort of Sovereign Chief, of course. There would be no takers. Financial troubles probably spurred on his dreams of wealth and fame ruling a far realm, though. In 1824, he was imprisoned for debt in London.

After traveling through America and the Caribbean with his wife and family ostensibly gathering supplies and supporters, or more probably simply escaping his bad finances and creditors in Europe, Thierry was finally off to the South Pacific in 1835. But not before briefly putting in an application for a concession to cut a canal through Panama. The Panama Canal was not even the last of his lofty ambitions along the way.

After he finally did arrive in Tahiti, he took the opportunity to proclaim himself the "King of Nuku Hiva” in the Marquesas Islands. Needless to say, he wasn’t taken especially seriously as king. His attempts to recruit a military force to claim his supposed sovereignty over New Zealand and its chiefs by force, if necessary, did start to raise some serious concerns with the British Resident at Waitangi and missionaries in New Zealand.

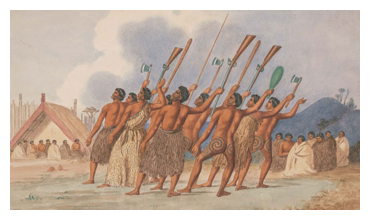

Thierry’s New Zealand folly finally evaporated after his actual arrival in 1837 when the local Maori chiefs refused his kind services to be their monarch and the motley contingent of sixty colonists he had picked up along the way in Tahiti and Australia rioted and fled.

Alarmed at the armed troubles Thierry was helping to stir up, and the lure of other European countries or foreign adventurers to the area, the British government was moved to formalize control of New Zealand by 1840. By all accounts, Thierry was a charming man and good conversationalist, if a bit eccentric and overly ambitious in his goals. He was given 800 acres by the Maori chiefs in pity for his troubles. And probably to make him and his exasperating claims just go away.

Despite the evaporation of his grand designs, Thierry remained in the British colony and eventually ended life in 1864 giving piano lessons in Auckland to make ends meet. Oh, except for a visit to California to pan for gold during the Gold Rush and a two-year stint at the French consulate in Honolulu on his way back. Sic transit gloria mundi.

As for Thierry's grand and fabulous coat of arms with fuchsias? The unknown artist who drew this quasi-royal heraldic achievement for him—complete with an amusingly exotic Maoriesque crown topping the shield—simply lifted the whole fuchsia and bird composition directly from an illustration in James Cook’s A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World (1777). That illustration was drawn after John Forster and his son, George, who were uncredited in the book. They had their own dispute with the Admiralty over payment.

The bird in A Voyage is identified as the “poe-bird”. The fuchsia as “Skinnera excorticata”, subsequently properly published as Fuchsia excordicata. Cook’s book would certainly have been readily available in London or Cambridge to serve as a model for both the unknown artist. And as fuel to fire the younger Thierry’s ardent and exotic dreams of riches and royal fortune in the South Seas.

(Illustrations: 1 & 6. Artist unknown. Tenax, Strength and Harmony. Armes du Baron de Thierry, Charles 1er, roi de la Nouvelle Zélande. Warner sc[ulpsit]. [London or Cambridge? ca 1825 or 1840]. Ref: A-320-026. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22851248. Detail of the tui-bird and Fuchsia excorticata. 2. Artist unknown. Pencil sketch of Charles de Thierry. Auckland City Libraries, 7-A10827; 3. The missionary Thomas Kendall visiting England with two Maori chiefs, Waikato. James Barry, oil on canvas, 1820. National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington NZ (Ref:G-618); 4. War dance with mixed Maori and European weapons, watercolour by Joseph Jenner Merrett, about 1845. Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia (Ref:nla.pic-an2948236); 5. Poe-Bird, New Zealand. James Cook, A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World, 1777. The plate shows a “poe-bird” perched on a flowering branch of Skinnera excorticata (Fuchsia excorticata) drawn after Forster & Forster.)