The color fuchsia

Thursday, November 15, 2012

One of the major frustrations for anyone who has ever searched for fuchsias on the Internet is the seemingly indiscriminate use of fuchsia to describe eye-popping brightish-purplish-violetish-pinkish hues. Maybe magenta. Sometimes cerise. But often just any plain-old pedestrian pink brightly tarted up for the catwalk.

From eBay to Esty, it seems impossible to cut through the pink clutter. Irritatingly, it’s also maddeningly misspelled as fuschia or fushia, or whatever & worse. In fact, if it’s misspelled you can largely assume the flashy color is being advertised.

How did this double life of naughty negligees and spiked heels, pink panties and lipstick, glowing fingernail polish and cellphone cases, all being offered in hot, flirty fuchsia come to be?

What? No color fuchsia? That seems odd, you say? Time to set the record straight. From Wikipedia to eHow, there is so much misinformation.

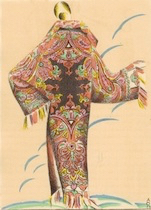

Fuchsias are certainly popular plants, from their first arrival in the greenhouse and garden in the late 1790s to the present day. Almost emblematic of the whole Nineteenth Century, in fact. On the fashion scene, they frequent embroidery and white lace, and their pendant blossoms dangle in fringes and tassels of all sorts. They adorn as jewelry and are cut into glass. And fuchsias were sometimes called Lady’s Eardrops. Brightly colored but perfectly ladylike, elegant and respectable. Even saintly at times. So what happened to that gentle, but consumptive and doomed soul at the heart of The Fuchsia—a sentimental tale of Victorian moralizing published in 1853—on her way towards the Twentieth Century?

A complete makeover, it seems.

And that novel sense of color, despite a few sporadic premonitions, had only just surfaced a couple of years before. Fuchsia quite literally burst onto the scene in the early 1890s, heralded from newspapers as

Fads. Fashion fads. Then as now.

Fuchsia-red emerged from a general embrace of various hues of red by trend-setting society ladies in the early 1890s. This trend was especially prominent—and noticed worldwide—at the Grand Pix de Paris of 1893. Fashion types of the age (as ever) looked for novel and tempting metaphors to describe newly chic

Similarly, Salammbô, the exotic Carthaginian heroine of Gustave Flaubert's eponymous historical novel first published in 1862, was briefly pressed into service as a shade of red in 1892. The color Salammbô was described as a “brilliant fuchsia tint” even. Far different from the Lady of the Fuchsias. What did she really have to do with red, though? Nothing. But she is, in fact, a real hint of a sexier, more salacious fuchsia to come.

So it goes over the next twenty years and trendy “Fuchsia-red" does manage to stage occasional reappearances into the Twentieth Century. In spite of the fact that fuchsias themselves

So, how could an outdated color associated with a fusty old flower come to be seen as so hot, hot, hot?

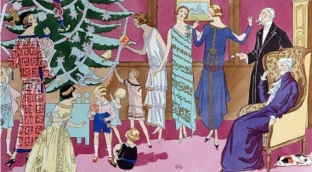

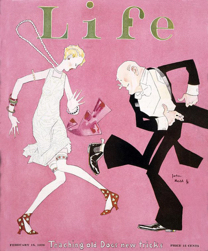

It’s really only starting in the late Teens into the early Twenties that the electrified, modern fuchsia finally, fully blossoms on the fashion scene. And it blossoms strongly when it does. At first, the myriad shades of fuchsia seem to be fighting it out. As late as 1923, London’s Daily Mail still reports “Colours: Peach, Apple, Apricot, Mauve, Fuchsia, Periwinkle.”

Something strange seems to be happening to the tint. Attention is definitely shifting away from the old-fashioned fuchsia-red of the flower’s sepals, focusing more brazenly on associations with sex; Certainly there have been sensual comparisons of the slow unfolding of the flower’s inner petals as the blossoms languidly split open. Or the faster sensual pleasures of popping fuchsia buds open. (And there’s also the issue of spelling and pronunciation, which lurks just below the surface and has always caused titters in English-speaking countries.) Emily Dickinson already caught on to the metaphors in one of her poems in 1862.

I tend my flowers for thee-

Bright Absentee!

My Fuchsia's Coral Seams

Rip-while the Sower-dreams-

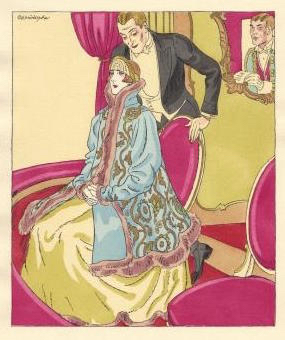

Fashion magazines increasingly use fuchsia to mean a new, stylishly bright magenta fabric, such as on a Lucien Lelong coat "with a quilted lining of fuchsia satin" featured in the Ladies Home Journal in 1925. Colorized illustrations of this elegant garment,

By 1930, the transformation seems complete. The appearance of the first edition of an influential new reference work, A Dictionary of Color, by Aloys Maerz and Morris Paul, codifies fuchsia/magenta as daring designers and trend-setters continuously reach for the seminal book to transfer its definitions from their shelves to their clothes. A second edition is released in 1950. Of course, fuchsia has become ever brighter and bolder since then. And more clichéed.

The revival had little to do with the actual flower. It was chemistry meets fashion.

By the Twenties, styles and tastes were rapidly moving beyond the drab days of WWI and that lost world of old. Through the decade, washes of vivid pink, cerise and magenta would enliven fashion plate after fashion plate. But these were NOT your grandmother’s garden colors. Or her fashion reds.

The new magenta/fuchsia of the modern age is much more daring and alive than that that old fuchsia could ever had been in its age of corsets and bustles. It was brash and frankly uninhibited. It was a bit naughty. Movies may still have been

Well… Almost never looked back.

Since 1859, in fact. About that year, the French manufacturer Renard Frères et Franc coined the trade name fuchsine for a synthetic red aniline dye, rosaniline hydrochloride, it manufactured. (The story of the rise and fall of Renard Frères, fuchsine and its involvement in early patent disputes and monopolistic sheenanigans is utterly fascinating but THAT will have to wait for another bog post.)

The chemical dye itself had been developed a little earlier. Rosaniline hydrochloride was first prepared in Germany in 1858 by August Wilhelm von Hofmann from aniline and carbon tetrachloride. Meanwhile in France, François-Emmanuel Verguin formulated the same substance independently that same year and patented it.

Renard Frères et Franc's choice of a trade name was influenced by the fact that fuchsias were simply a fashionable garden plant—and not really intended as a reference to the actual color of some of its flowers—and that Fuchs, which means fox in German, conveniently translated into French as Renard, or fox. Fuchsine. Part fashion, part fox. This isn’t even speculation. The firm itself stated the motivation behind the name in 1861. With the contemporary taste for fuchsias very much still on the rise in gardens and on windowsills, the new trade name was a brilliant marketing ploy to sell the dye they manufactured. Even if the exact color match was a bit dodgy. Interestingly, the original association of the first part of the chemical name, rosaniline, is to the bright pink of some roses.

Yet oddly, fuchsia the color was spreading and thriving. The fuchsine used by the fabric industry (often misspelled fuchsin) almost certainly had a direct influence on the sudden and strong appearance of fuchsia as a chic color name standing alone. But this time fuchsia was a very brilliant, pure magenta rather than a duller purple-red. The modern perception of fuchsia undoubtedly directly followed from the use and name of this old industrial dye, fuchsine, and the increasing trendiness of the strong colors it could produce, rather than from any real association with the momentarily fusty old garden flower.

No doubt much fuchsine-dyed cloth simply became fuchsia-colored clothes. It certainly sounded prettier and was easier to say. Realizing the role fuchsine played in the development of the concentrated modern fuchsia/magenta also helps explain why observers are often so puzzled as to how that extreme fuchsia color could have come from that fuchsia flower. Fuchsine, by the way, is still around in several different chemical formulations. It’s also used as a cell stain in biology and, surprisingly, sometimes as a disinfectant.

Each decade since has seen similar attempts but they just seem weaker and weaker as the hue gets hotter and hotter, growing ever more desperate for attention. And now we have the Internet and eBay… Oh well. Today, fashion fuchsia is even considered a slightly less saturated hue than fuchsia and it's synonymous with Hollywood cerise, or sometimes simply Hollywood, in the fashion world.

P.S. The “Fusha” image at the top is indeed an actual restaurant in Manhattan. And, OK, I admit it, I couldn't resist eating there. Despite the annoying and dumbed-down spelling, the pan-Asian food's really not bad at all. I quite enjoyed my duck & night-market-noodley dish. Just tell ‘em FUCHSIAS in the City sent you, if you happen by for a meal.