Bracie's fuchsia

Wednesday, August 14, 2024

Plant names in botany can often seem alien or inscrutable, as if they landed on Earth on a scrap of paper fallen from the pocket of John Carter of Mars, or hitched a ride from the highest heights of Tibet, unnoticed in the dusty, adventure-battered baggage of Indiana Jones. What is Metasequoia glyptoboides, anyway? Some antediluvian holdover from the age of the dinosaurs found in a lost valley in central China? Well, actually, yes. But that’s another story… (Another story: ➤ The Dawn Redwoods of Munnysunk)

Some botanical names might be familiar to general readers of Latin: Quercus is simply the oak and Fagus, the beech. When Latin, the international language of all science and learning in the Middle Ages, was naturally put to use as the language of the science of early botany, the old names became new, scientific ones. Add a dash of rubra to that Quercus, shake and, ecce, the red oak!

Of course, the world was a lot larger than the fields and forests of old Europe and wonderful new plants that would have delighted even Pliny, had he actually had names for them, soon came pouring in from its four corners. Not to be struck too dumb and in awe of such burgeoning riches, the doctors of learning simply continued muttering amongst themselves, describing things in their handy old Latin, as they had done since the fall of Rome, inventing new names for new plants from their linguistic stock of Latin. Adding names from Greek and a few other languages along the way.

Fuchsia is adapted into botany from the Latinized German word for fox, Fuchs. (Don’t worry about your pronunciation of the actual German: If you say it to rhyme with “books,” it’s close enough to pass muster.) It was pressed into service by Charles Plumier to honor an earlier doctor of medicine and botany named Leonhart Fuchs, or Leonardus Fuchsius, as he was known among his Latin-spouting peers on the campus quad of nearly any university from Kraków to Salamanca. It’s an appropriate honor as well, as he’s considered one of the three fathers of modern botany, even if he did it all in old Latin. And so it continues.

When botanists get bored of appending simple, common-sense descriptions to new species, such as Fuchsia excorticata, that fuchsia with lots of exfoliating bark hanging down its truck in strips, or Fuchsia macrostigma, the one with a really big stigma sticking out of its blooms, then they might reach to a location. Fuchsia magellanica, the fuchsia from the Straights of Magellan, or Fuchsia ayavacensis, the one from Ayabaca. Ayabaca, you say? Yes, of course. From that very same hot spot of botanical nightlife in provincial Peru. Over by the border with Ecuador. Up in the mountains. Sí, THAT Ayabaca!

Sometimes an honorable name will get another honorable epithet tacked on to become something of a two-headed honor. (Occasionally even three heads if you toss in a subspecies.) Fuchsia glazioviana is Glaziou’s Fuchsia (or really Glaziou’s Fox’s Flower if you want to be picky). These flourishes go well beyond the actual plant and often harbor hidden tales tucked behind the seemingly odd and unpronounceable names. Auguste François Marie Glaziou (1828-1906) was a French landscape designer and botanist who was lured to Brazil in 1858 by Emperor Dom Pedro II to be his director of parks and gardens in Rio de Janeiro. He designed the grounds of the Imperial Palace of Saint Christopher (Paço de São Cristóvão) at the Quinta da Boa Vista. A plant collector in his own right, Glaziou returned to France in 1897 to work on his herbarium. His fuchsia species was first published in 1892 by a German botanist working in Brazil, Wilhelm Taubert (1862-1906). The connection and the honor make perfect sense when you realize that Fuchsia glazioviana was discovered growing in the mountains nearby Rio de Janeiro, around the towns of Nova Friburgo and Santa Maria Madalena.

Fuchsia bracelinae? Like Fuchsia excorticata or ayavacensis or glazioviana, what, where or who on earth is this fuchsia? And how does one get one’s tongue around a bracelinae, anyway? Of course, there’s another tale of dedication and life-long service to the field of botany memorialized behind this name as well. The pronunciation is simple, since it’s just Bracelin’s Fuchsia in plainer English. And the plant might go by Bracie’s Fuchsia, as well, as that was how Mrs. N. Floy Bracelin was usually known to her friends. (She's often listed as Nina Floy Perry Bracelin but that's not how she actually styled herself.) As a matter of fact, two tales are hidden here, as the role played by the colorful and larger-than-life Mexican-American plant hunter, Ynés Mexía, is an integral part of the story.

After divorcing her second husband in Mexico and suffering from depression, Mexía moved to San Francisco, where she only actually started hunting plants in 1922, at the age of fifty-two. However, she managed to log five expeditions to Mexico, four to South America and even one to Alaska (simply because she had never been there and wanted to see it) before she died in 1938, aged sixty-eight. While she was friends with the renowned botanist Alice Eastwood (1859-1953), many fellow plant hunters and botanists often found the aristocratic and prickly Mexía moody and hard to endure on expeditions. Several she simply organized on her own.

Like many forces of nature, Mexía was also much better at orchestrating Sturm und Drang than the aftermath. She loved finding new things (five hundred new species in all) and lecturing later about the excitement and hunt before a slide lantern. But she seems to have found putting those finds into any useful state and dispersing them to herbaria a chore she didn’t especially relish. Despite having attended a number of prestigious private schools in the United States and Canada, St. Joseph’s College and then courses at the University of California, Mexía seemed only a passable student and the class where she met Bracelin had evidently been an attempt to improve her methodology.

In December 1943 the Academy published it’s Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences as a Festschrift celebrating Alice Eastwood's fifty years as curator of botany. Among the contributors was Phillip A. Munz (1892-1974), who used the occasion to publish "A Revision of the Genus Fuchsia (Onagraceae).” This article would be a ground-breaking effort that brought much-needed clarity and order to the genus and is really the starting point of its modern scholarship. Working from the collections made by Mexía in open campo de altitude on the Serra do Caparaó in Espiritu Santo, Brazil in 1927 and prepared and distributed by Bracelin in 1929, Munz recognized that he actually had an entirely new species in front of him rather than the provisionally labelled Fuchsia pubescens. His dedication of Fuchsia bracelinae reads, "It is a pleasure to dedicate this species to Mrs. H. P. Bracelin of Berkeley, California, who has devoted much time and energy to distributing the large collections made in Latin America by Mrs. Mexia.” (Unfortunately, another new species also collected by Mexía in 1927 but this time in a canyon at San Sebastian in Jalisco, Mexico—which Munz premiered in the same article as Fuchsia mexiae—has turned out to be the already published Fuchsia cylindracea.)

In all, Nina Floy Bracelin would be honored by various botanists in the names of three additional new species of plants bedsides Bracie’s Fuchsia.

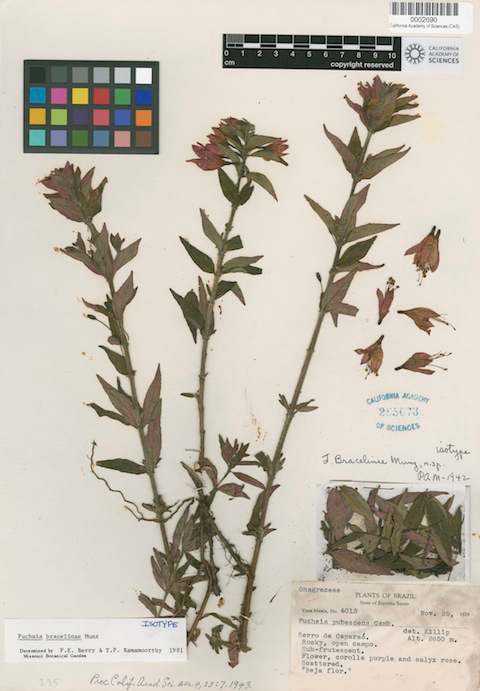

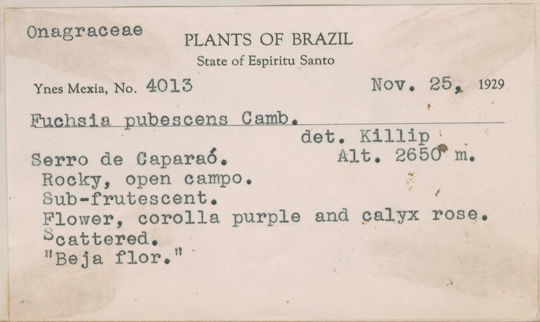

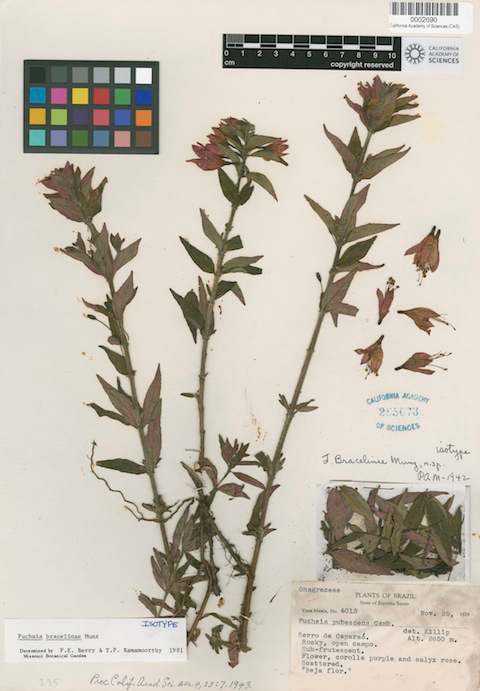

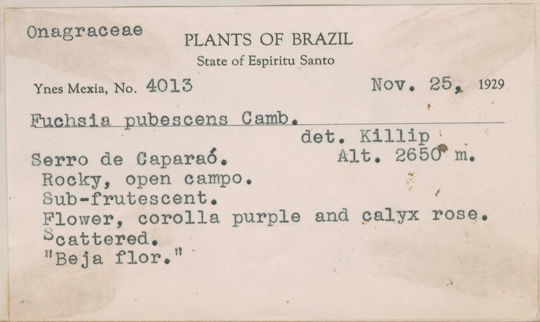

(Illustrations and credits: 1-11. Details of Fuchsia bracelinae from the 1927 collection made by Mexía in Brazil and distributed by Bracelin to the ➤ California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, the ➤ Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Loius, the ➤ University of California at Berkeley and the ➤ US National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. among other institutions; 12. An isotype of Fuchsia bracelinae housed at the ➤ California Academy of Sciences; 13. A typical herbarium label prepared by Bracelin to accompany Mexía specimen sheets. This label provisionally identifies, as Fuchsia pubescens, the specimen which Munz was to publish in 1943 as Fuchsia bracelinae; 14. (Below) The 1916 California Academy of Sciences building as it would have appeared when Nina Floy Bracelin was active. Unfortunately, the Academy suffered significant earthquake damage in 1989. The glittery new building which opened in 2008 is very green and houses a number of nice, educational theme parks.

The Fuchsia+Blog Tags — fuchsias | species