Alice Eastwood. Earthquakes and fuchsias

Amazingly, her early botany was self-taught. Using books such as Asa Gray's Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States and John M. Coulter's Manual of the Botany of the Rocky Mountain Region, she achieved such competence and knowledge in the field that she was asked to guide the celebrated botanist, Alfred Russel Wallace, one of the co-founders of evolutionary theory through natural selection with Charles Darwin, to the top of Grey’s Peak when he visited Denver in 1887.

In 1891, Eastwood did just that before returning to Denver with the intention of devoting herself to he flora of Colorado and the deserts of Utah. In 1892, however, she instead came back San Francisco and assumed a post in the Academy’s herbarium. Brandegee would take a cut in her own pay to take her on. Eastwood was quickly promoted to a position as joint Curator of the Academy with Brandegee. By 1894, on the resignation of Brandegee from the Academy to move to San Diego, Eastwood was to become procurator and head of the Department of Botany, a position she held until she retired on her ninetieth birthday in 1949.

After the shaking, she rushed to the Academy building then on Market Street, where a small group of its curators and assistants had assembled, only to find the stairway in the central court partially collapsed. Using ropes, Eastwood and a helper quickly lowered as much of the herbarium’s contents as they could before the spreading fires cut short the full rescue of the rest. While much was lost, her unconventional organizational system enabled her to retrieve almost fifteen hundred of the invaluable and irreplaceable type specimens from the building in short-enough time to take them to safety. She also managed to save the early records of the museum. The museum’s library and most of its natural history collections would be destroyed in the fires, however.

Eastwood took on the reconstruction with her usual boundless enthusiasm and physical energy. She went on numerous collecting vacations, financed from her own pocket, in the Western United States to visit Alaska, Arizona, Idaho and Utah. From her visits, she kept the first sets of the thousands of sheets of western flora she collected for the Academy and exchanged her duplicates with other institutions. By 1942 she had rebuilt the Academy’s herbarium to about 340,000 specimens, nearly three times the number destroyed in the devastation of 1906.

In addition to her assiduous collecting, Eastwood published well over three hundred articles during her long career. Quite a number were written for a popular audience to promote plants and botany. Her main botanical interests were the Liliaceae of the Western United States, as well as the genera Lupinus, Arctostaphylos and Castilleja. She also worked as an editor on several editions of Zoe: A Biological Journal (published by the Townshend Brandegee from 1890-1906), as an assistant editor for Erythea: A Journal of Botany, West American and General (published by the University of California Berkeley from 1893-1900 and 1922), and founded the journal,

Among her many, many achievements in botany, Eastwood was one of the founding members of the American Fuchsia Society in 1929. She also was instrumental in holding the young Society together in its early years as a number of its original eleven members fell away. For the quickly undertaken census of fuchsias growing in gardens and nurseries in California, she instructed society members and others on how to properly take and mount specimens to send to her at the Academy. In 1931, she published "True Species of Fuchsia Cultivated in California" (National Horticultural Magazine, 10:2:100-104).

Despite most of a lifetime spent in San Francisco, and her decades-long dedication to that city and the native plants of California and the West, the pioneering Eastwood was oddly to be buried In Toronto after her death in 1953. She now rests under a simple, nondescript flat marker in ➤ Toronto's Necropolis, in a city that she had left behind at the age of fourteen.

The San Francisco Botanical Garden, however, does have the Alice Eastwood Garden established there in her honor by the San Francisco Garden Club in 1971. She was an early president and life-long member of the organization and the garden is appropriately planted with fuchsias. Its bronze marker seems more suited to the spirit of her life, even if it doesn't cover her actual remains.

Alice Eastwood was born on January 19, 1859 and today marks the 157th anniversary of her birth. Happy Birthday, Alice Eastwood, either in your fuchsia garden or your redwood grove!

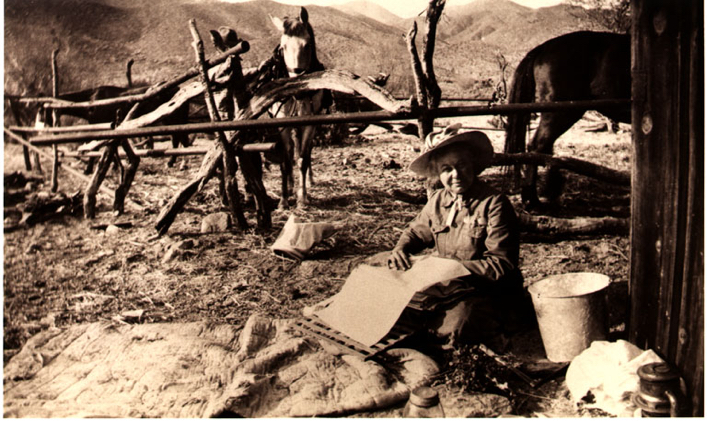

(Illustrations: 1. Alice Eastwood at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS). Imogene Cunningham, 1953, Eastwood Papers, CAS; 2. Portrait of Eastwood in a floral hat. CAS Cat. No. N5116c. Gustavus A. Eisen. About 1909-1912; 3. Partially collapsed courtyard of the original California Academy of Sciences after the devastating 1906 earthquake; 4. Fires sweep San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906 quake. Library of Congress; 5. & 12. Eastwood viewing a rift caused by the earthquake in the Olema Valley north of San Francisco. G. K. Gilbert, U.S. Geological Survey, 1906; 6. Eastwood with plant press, Warner Hot Springs, San Diego County, 1913, Eastwood Papers, CAS; 7. Eastwood with her plant press, 1927, Eastwood Papers, CAS; 8. Sorting botanical specimens in the field in 1929, the year she helped found the American Fuchsia Society. MSS. 142, Eastwood Papers, CAS; 9. & 10. Bronze memorial marker and view of the Alice Eastwood Garden at the Styrbing Arboretum; 11. The botanically inclined ex libris with a California landscape that marked Eastwood’s books.)