The Inca and the Fuchsia

Saturday, June 20, 2020

While superficially similar, Fuchsia boliviana should not be confused with Cantua buxifolia, a member of the phlox family and the so-called sacred flower of the Incas, Cantua is found growing in high valleys of the Yungas and is a national floral symbol in Peru and Bolivia. Known as Qantu, Qantus or Qantuta in Quechua, other common names include flor del Inca, magic-flower, magic-flower-of-the-Incas, magic-tree, and sacred-flower-of-the-Incas. Associated with perhaps the sun, purity and water, the Incas used it in rituals and ceremonies. Even long after the Inca period, the flower was found at funerals in the belief that the dead would quench their thirst on their journey into the afterlife by drinking its copious nectar. The cantuta continues to be a common decorative motif in traditional arts and crafts.

Chimpu-chimpu, on the other hand, might have had a more direct symbolic association with the Sapa Inca ruler himself. Indeed, Fuchsia boliviana remains one of the characteristic plants found along the roads and paths leading to Machu Picchu. The corolla around the sun’s disk was known as the Inti chimpu: The rays or fringe of the Sun God, Inti. Similarly a red fringe on the multicolored royal headband appears across the forehead of the Sapa Inca as part of his imperial regalia. His face is surrounded with the rays of the Sun, linking him directly to the most important and venerated god of the Inca pantheon. And serving as a constant reminder to those that gaze at him just whom he represents.

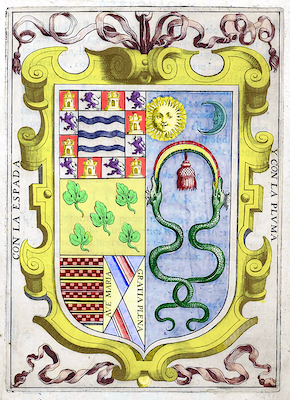

Of recognized nobility, Garcilaso certainly had inherited a coat of arms from his father. On his shield, however, Garcilaso impaled these paternal arms with what would seem to be attributed arms representing his mother or her family. Since he was illegitimate, and not the main heir to his father and his family, it would have been normal to mark his paternal arms with some difference in this way. Interestingly, the main charge of these maternal arms resting on an azure blue field depicts a rainbow being swallowed at both ends by two crowned serpents. An impressive red tassel dangles from the middle of the rainbow between the two snakes. The chief is further charged with a golden sun and a silver moon in opposite corners.

There are certainly mythological references in the composition but it seems the main charge is also a direct attempt to represent the regalia and headdress of the Sapa Inca. As an imperial symbol, it’s the equal of any double-headed eagle, purple lion or golden castle. A crown in the form of a multicolored headband of the rainbow, mythological snakes serving as ties, and, though reduced to a single large red tassel, marked with the rays of the Sun God himself. The regalia of a once powerful, if now conquered, empire. For Garcilaso, it’s an imperial vindication of his illegitimacy.

There are other contemporary arms attributed to the Inca rulers than those that appear on the sinister flank of Garcilaso’s shield. He might well have introduced those arms as a quartering along with his paternal quarters as an acceptable difference. Impalement is usually a matrimonial arrangement, uniting two matrimonial coats of husband and wife on a single shield. The red tassel is a direct allusion to his royal mother, Isabel Chimpu Ocllo. Could El Inca have been displaying his parent’s union as heraldically legitimate even if it wasn’t legally? As a young boy he certainly suffered his father’s neglect and then his outright rejection of his mother. It’s an interesting possibility.

(Illustrations: 1. Thomas Blackshear, Hiram Bingham's Discovery of Machu Picchu, Peru in 1911; 2. Detail. Fuchsia boliviana Carrière, Revue Horticole, serié 4, vol. 48, 1876; 3. Arms of ➤ El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616); 4. Portrait of El Inca Garciloso de la Vega with his arms.)