A Dictionary of the Fuchsia™

Want to know what those mysterious terms mean and just who the people were behind those names? Then this is the place for you.

Want to know what those mysterious terms mean and just who the people were behind those names? Then this is the place for you.

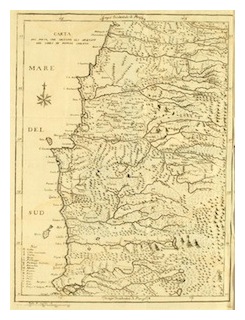

Lady's Eardrops – According to most reference works, Lady's eardrops is the so-called common name for the fuchsia in English. Despite this frequent assertion and repitition, the name isn't now, nor ever was it ever, common. It can be considered defunct in usage. The name might have originated as an early borrowing from the Spanish Pendientes de la Reina, or perhaps the Portuguese Brinco-de-Princesa. These two languages provide intriguing hints to a link with the mysterious introduction of either one of the first two fuchsia species grown in English gardens, though: F. magellanica from Chile or F. coccinea from Brazil. Or perhaps to both more-or-less simultaneously since confusion between the two very similar-looking species was also early and widespread. Whatever the suggestive origin, English speakers have always shown a marked preference for using fuchsias over Lady's Eardrops and the term never gained as much currency as would be surmised from the seemingly ubiquitous assertions. Articles, reference works or databases that accord it primacy as anything more than a curiosity should be approached with caution as the information is almost certainly culled from other works and not necessarily based on experience or research. Lady’s Eardrops is sometimes reported to specifically refer to F. magellanica, as F. coccinea has been frequently translated into the “scarlet fuchsia” in older writings. It is also found as Lady's Eardrop, Ladies' Eardrop or Ladies' Eardrops, with or without various hyphenations. See also The Urban Fuchsia + Blog ➤ What's in a name?

(Illustration: Detail from the "Flower Ball" illustrated in J.J. Grandville's Les Fleurs Animées, 1847.)

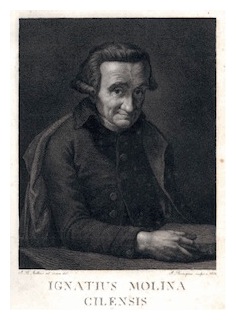

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1744-1829) – Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, the Chevalier de la Marck, known simply as Lamarck, was a French naturalist and early proponent of evolution. Born to an impoverished military family, Lamarck was originally designated by his father for a career in the church. After his father's death, however, he quickly left his Jesuit college to join the army. He eventually took up the study of botany after he was retired due to injuries in

Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1744-1829) – Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, the Chevalier de la Marck, known simply as Lamarck, was a French naturalist and early proponent of evolution. Born to an impoverished military family, Lamarck was originally designated by his father for a career in the church. After his father's death, however, he quickly left his Jesuit college to join the army. He eventually took up the study of botany after he was retired due to injuries in  1766. The publication of his three-volume work Flore Française in 1778 gained him much recognition. Lamarck was eventually named a royal botanist and by 1788 appointed the keeper of the herbarium at the Jardin du Roi. During the French Revolution in 1790, he changed its name to the Jardin des Plantes to distance it from the king. In 1793, he was appointed professor of invertebrate zoology in charge of insects and worms at the new Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, which he had helped reorganize from the Jardin des Plantes, and became interested in evolutionary theory while studying mollusks in the Paris Basin.

1766. The publication of his three-volume work Flore Française in 1778 gained him much recognition. Lamarck was eventually named a royal botanist and by 1788 appointed the keeper of the herbarium at the Jardin du Roi. During the French Revolution in 1790, he changed its name to the Jardin des Plantes to distance it from the king. In 1793, he was appointed professor of invertebrate zoology in charge of insects and worms at the new Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, which he had helped reorganize from the Jardin des Plantes, and became interested in evolutionary theory while studying mollusks in the Paris Basin.

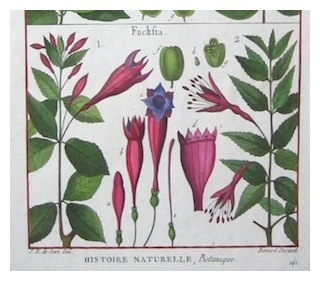

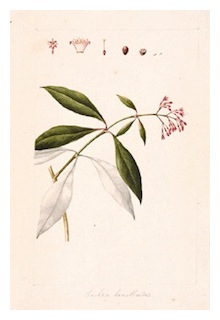

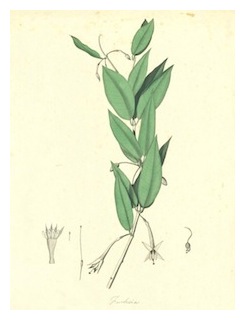

While Fuchsia magellanica had been collected as early as 1690 (see Handyside), and Louis Feuillée observed it as Thilco in 1714, Lamarck was the first to formally publish F. magellanica as a species in 1788. The holotype resided in the Jardin’s herbarium but had been collected two decades earlier in 1768 by Philibert Commerçon (also spelled Commerson) in the Straights of Magellan. Commerçon was the French naturalist who had accompanied Louis Antoine de Bougainville on his circumnavigation of the globe from 1766–1769. Commerçon died in Mauritius in 1777 and his papers and collections were forwarded to Paris after his death.

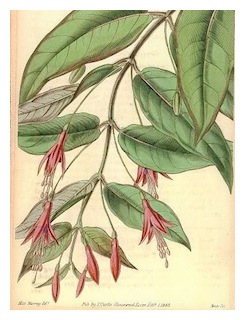

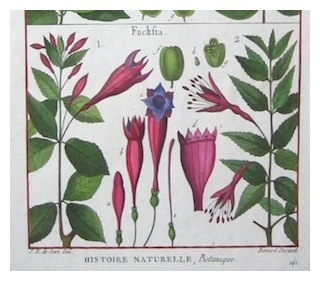

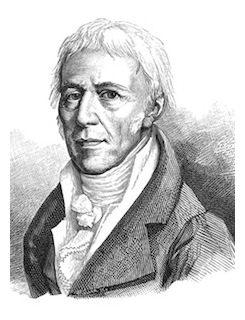

(Illustration: 1. Fuchsias in Histoire naturelle, 1788; 2. Portrait of Lamarck from J. Pizzetta, Galerie des naturalistes, Paris, 1893.)

Lamb, Jack – ➤ See National Collections (UK).

Lampadaria – F. lampadaria (J.O.Wright 1978) is a synonym of F. magdalenae (Munz 1943) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Lanceolate – Lance or spear-shaped. The term is applied to fuchsia leaves with this general outline.

Lectotype – The botanical specimen selected as the type specimen for a species when a ➤ holotype hasn't been defined.

Lee, James (1715-1795) – Prominent Scottish-born plantsman who in 1745 became partner with Lewis Kennedy (1721-1782) to found the nursery firm of Lee & Kennedy. Their famous nursery grounds, called the Vineyard, were located in Hammersmith. The firm spanned three generations and the location at the Vineyard was active until 1885 when the site was developed for Olympia Hall.

Lee, James (1715-1795) – Prominent Scottish-born plantsman who in 1745 became partner with Lewis Kennedy (1721-1782) to found the nursery firm of Lee & Kennedy. Their famous nursery grounds, called the Vineyard, were located in Hammersmith. The firm spanned three generations and the location at the Vineyard was active until 1885 when the site was developed for Olympia Hall.

Lee apprenticed under Phillip Miller (see also) at the Chelsea Physic Garden and served as gardener to the Duke of Somerset at Syon House and, later, the Duke of Argyll at Witton Park. He corresponded with Linnaeus and published An Introduction to Botany in 1760, explaining the Linnaean system to a wide public. The book went through through five editions. Lee also corresponded with botanical collectors in the Americas and tested the hardiness of plants in England from the Cape of Good Hope. The firm had many prominent admirers and customers including the French Empress Josephine and the Russian Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna, who made a special stop at the nursery when Czar Alexander I visited England. He was succeeded at the firm by his son, also named James Lee (1754-1824).

The nursery is credited with the introduction of Fuchsia magellanica (often confused with F. coccinea at the time) into popular cultivation. According to variously repeated tales, the novel plant was first noticed on a Wapping windowsill, sometimes that of a certain Captain Firth's mother (see also Firth), or at other times just a sea wife's or widow's, by either the elder or the younger Lee. It was supposedly bought from her for the princely sum of £15 to be propagated and sold by the firm in 1788 for an equally step guinea a plant.

This origin story is colorful, but mysterious, late and likely apocryphal, and it's been suggested that it was invented to cover the questionable liberation of cuttings from Kew. However, considering the extensive and exceptionally prominent botanical and horticultural connections of especially the senior Lee, that suggestion is highly implausible. The firm did also introduce dozens of other novelties, such as the dahlia in 1818, to the public.

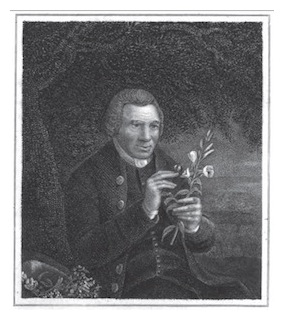

(Illustration: Portrait of Lee from An Introduction to Botany, 1760.)

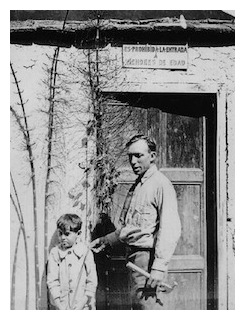

Lehmann, Federico Carlos (1914-1974) – Also sometimes known as Friedrich Karl Lehmann. Lehmann was a Colombian ornithologist, plant collector and conservation biologist. He was born in Colombia to a German father who died while exploring the Río Timbique. Following early schooling in Berlin, he returned to Colombia in 1929 to study at the University of Cauca in Popoyán

In 1938 Lehmann accepted a job in the Institute of Botany at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá, where he was in charge of its collection of animal specimens. On his travels through the country to expand the collection, he became increasingly interested in ornithology and in environmental protection and worked to promote conservation legislation in Colombia during the 1940s and 50s.

From 1956 to 1961 Lehmann was the assessor of natural resources for the Ministry of Agriculture in Valle and Cauca and his efforts lead to the creation of several new protected areas, including the Farallones de Cali National Natural Park, the Laguna de Sonso Nature Reserve, the Los Nevados National Natural Park and the Puracé National Natural Park.

He founded the departmental Museum of Natural Sciences in Cali in 1963. It was renamed in his honor after his death in 1974. He was also commemorated in the name of Lehmann's Poison Frog (Dendrobates lehmanni).

See F. lehmannii in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

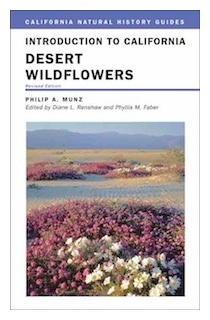

Lehmannii – Named in honor of Federico Carlos Lehmann (1914-1974). See ➤ Lehmann; F. lehmannii (Munz 1943) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Leicester, University of, National Collection of Hardy Fuchsia – ➤ See National Collections (UK).

Lemoine, Victor (1823-1911) – Exceptionally prolific French flower breeder and nurseryman in Nancy, France. Lemoine worked on an astonishing number of garden species, but was especially noted for his lilacs, of which his nursery probably produced over two hundred hybrids including the first double. His achievements and fame spread widely and he would be awarded many medals, from the Royal Horticultural Society in London to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in Boston, for his outstanding achievements. In 1885 he was made a member of the Legion of Honor by the French government, being elevated to the rank of knight officer in 1894. The family firm survived until 1960, when it was finally closed.

In 1885 he was made a member of the Legion of Honor by the French government, being elevated to the rank of knight officer in 1894. The family firm survived until 1960, when it was finally closed.

Starting about 1855, and quickly picking up steam, Lemoine began regularly releasing new fuchsias to an eager public every year. The pace continued for almost six decade and only his death put an end to the stream. By some estimates he was eventually responsible for almost four hundred and fifty hybrids. A hundred or more seem to have gone lost but many are still very popular and widely grown in gardens. Among them are such recognizable favorites as Abbé Farges, Baron de Ketteler, Brutus, Caledonia, Carmen, Dr. Foster, Dollar Princess, Drame, Enfant Prodigue, Fascination, Graf Witte, Heron, Isabelle, Jules Daloges, Lord Byron and Pénoménal. The list goes on and on. On and on below, in fact, even though this extensive list is hardly complete. It's interesting to note that many of his creations were named after well-known celebrities and luminaries of his day, even if they're no longer household names. Lemoine was an astute businessman, after all, and was obviously not adverse to the free publicity their namesakes provided. A number of his fuchsias have also become widely know by the English versions of their names.

List: Château Briand (1847), Mademoiselle Octavie (1854), Tardif (1856), Pénélope (1857), Atropurpurea Plena, Lamartine, Monstruosa Flore Pleno, Reflexa Flore Plana (1858), Comte de Medici Spada, Léonard de Vinci (1859), Solferino (1860), Baron Gros, Victorien Sardou (1861), Amandine Hans, Charles XII, Eugène Bourcier, Fille de l'Air, Président Porcher, Rhoda (1862), Ami Hoste, Christian IX, Madame Boucharlat (1863), Barbe-bleue (1864), Béranger, Madame A. Delaux, (1865), Adolphe Weich, Brennus, Henri Jacotot (1867), Abel Cárrière, Harvin, J. N. Twrdy, Ruy Blas (1868), Jocelyn, Othello, Phénoménal (1869), Concile, Port Said, (1870), Bleu/Blue Phénoménal, MacMahon, (1871), Claude de Lorraine, Blanc/White Phénoménal (1873), Alsace-Lorraine, Commandant Taillant, Démosthène, Député Teutsch (1874), Burnouf, Bussière, Carpeaux, Croce Spinalli (1876), Coleridge, La Nation, Lord Byron (1877), Capitaine Boynton, Charles Darwin, De Candolla, Édouard André (1878), De Montaliviet, Francis Magnard, Francisque Sarcey, Littre, Pierre Joigneaux, Libuse (1879), Abd-el-Kader, Alphonse Daudet, Castelar, Dr. Crevaux, Drame, Gustave Doré, Isis, Nouveau Mastodonte (1880), Député Berlet, Gracieux, Jules Ferry, Pascal (1881), Agnes Sorel, Alfred Dumesnil, André Gill, Armand Carrel, Charles Blanc, Général Sassier, Parachute, Zampa (1882), Général Lapasset, J. J. Rousseau, Jeanne d'Arc, Lameunais (1883), Amiral Coubert, Arlequin, Auguste Flemeng, Député Voix, Flocon de Neige (1884), Fleur Rouge, Formose, Général Lewal, Indo-Chine, La France (1885), Amiral Moit, Auguste Renold, Bulgarie/Bulgaria, Colonel Domine, Élysée, Général Hoche, Hoche, Télégraphe (1886), Bartholdi, Buzenval, Enfant Prodigue, Fille des Champs, L'Enfant Prodigue, Mrs. E. Hill, Prodigue, Profusion (1887), A. de Neuville, Augustin Thierry, Ernest Renane (1888), Aerostat, Cervantes, Esperance, Gladiator, Minstrel, Néron/Nero (1889), Thérèse Dupuis, Albion, Buffon, De Athay, Dr. Prillieux, Dr. Topinard, Monsieur Joule (1890), Admirable Olry, Aimé Millet, Alphonse Karr, Amiral Aube, Céline Mantaland, Eugène Delaplanche, Gustave Flaubert, Heron (1891), Artemise, Auguste Hardy, De Quatrefages, Émile Bayard, Eugène Verconsin, Monsieur Alphard, Véra Sergine (1892), Albert Delpit, Bouquet, Carmen, Comte Leon Tolstoi, Lucie, Monsieur Hermite, Pasteur (1893), Adrien Marie, Capitaine Binger, Corne d'Abondance, Félix David, Félix Dubois, La Pompadour, Lieutenant Maritz, Lieutenant Mizon, Madame Moire, Marcel Monnier, Marcel Prevost (1894), Adrien Berger, Alexander Dumas (Alexandre Dumas), Lansdowne, Louis Figuier, Madame Carnot, Monsieur Gladstone, Président Burdeau, Triphylla Hybrida (1895), Alfred Rambaud, De Cherville, De Concourt, De Goncourt, Duc d'Aumale, Frère Orban, Garnier-Pagès, Gerbe de Corail, Miniature, Minos, Norma, Royal Purple (1896), Beaumarchais, Brutus, Corneilla, Florian, Molière, Monsieur Molier, Racine, Ronsard, Victor Hugo, Voltaire (1897), Alfred Fouillée, Colibri, Elsie Vert, Léo Delibes, Ministre Boucher, Monsieur Thibaut (1898), Comte Witte (a. k.a. Graf Witte), Alphand, Blanche de Castille, Caledonia, Carmen Sylva, Charles Garnier, Charles Samoureux, Colonel de Trentinian, Commandant Marchand, Dr. Foster, Général Gallieni, Monsieur Boucher, Nestor, Prince Georges, Sarah Bernhardt (1899), Charles Lamoureux, Madame Delina, Sculpteur Bartholomé, Statuaire Dalou (1900), Abbé Farges, Baron de Ketteler, Fleur Bleu, Général Voyron, Isabelle, Nautilus, Président Félix Faure, Stephen Pichon, Takou, Tien Tsin, Vincent d'Indy (1901), Dorothea Foubert, Dr. Behring, Frederick Passy, Héritage, Hugh Dutterail, Prix Nobel, Professeur Roentgen, Sully Prudhomme, Van t'Hoff (1902), Auguste Holmes, Émile Eskmann, Molesworth, Rochambeau, Rouget de l'Isle, Théroigne de Méricourt (1903), Armand Gautier, Émile Laurente, Le Robuste, Lucien Daniel, Pierre Mouillefert, Rhombifolia, Yves Delage (1904), Elfrida, Émile de Wildeman, Fascination, Fouvières, Henri Poincaré, John Lindsay, Leclerc du Sablon, Lecocq de Boisbaudram, Madame de Thèbes, Marcellin Berthelot, Naegeli, Phyrne, Pierre Bonnier, Rose Ballet Girl (1905), Alfred Picard, André Carnegie, Bertrade, Etienne Larny, Lucile Desmouling, Miarka, Monsieur Revoil (1906), Alfred Neymarck, Capitaine Tilho, Émile Lemoine, Émile Richebourg, Jules Daloges, Paul Meyer, Rose Porter (1907), Amiral Evans, Colonel Branlières, E. Joubert, Général d'Amade, Madame Eva Boye (Eva Boye), Susan Pasquier, Torpilleur, Voile Bleu (1908), Abbé David, André le Nostre, Juliette Adams, Lord Roberts, Paul Cambon, Professeur Lippman (1909), Émile Zola, Francois Boucher, Luc-Oliver Merson, Madame Thibault, Raoul Pugno (1910), Athènes, Calchas, Corinthe, Délos, Lacédémone, Messène, Sérervine (1911), Dollar Princess/Dollarprincessin, Dr. Bornet, Emma Calvé, Lucienne Bréval, Madame Lantelme, Rachilde (1912), Éliane, Fémina, L'Amoureuse, Madame du Gast, Madame Jacques Feuillet, Phoenix (Phénix), Rolla, Thaïs (1913), Firmin Gémier (1914).

Édouard André (1878), De Montaliviet, Francis Magnard, Francisque Sarcey, Littre, Pierre Joigneaux, Libuse (1879), Abd-el-Kader, Alphonse Daudet, Castelar, Dr. Crevaux, Drame, Gustave Doré, Isis, Nouveau Mastodonte (1880), Député Berlet, Gracieux, Jules Ferry, Pascal (1881), Agnes Sorel, Alfred Dumesnil, André Gill, Armand Carrel, Charles Blanc, Général Sassier, Parachute, Zampa (1882), Général Lapasset, J. J. Rousseau, Jeanne d'Arc, Lameunais (1883), Amiral Coubert, Arlequin, Auguste Flemeng, Député Voix, Flocon de Neige (1884), Fleur Rouge, Formose, Général Lewal, Indo-Chine, La France (1885), Amiral Moit, Auguste Renold, Bulgarie/Bulgaria, Colonel Domine, Élysée, Général Hoche, Hoche, Télégraphe (1886), Bartholdi, Buzenval, Enfant Prodigue, Fille des Champs, L'Enfant Prodigue, Mrs. E. Hill, Prodigue, Profusion (1887), A. de Neuville, Augustin Thierry, Ernest Renane (1888), Aerostat, Cervantes, Esperance, Gladiator, Minstrel, Néron/Nero (1889), Thérèse Dupuis, Albion, Buffon, De Athay, Dr. Prillieux, Dr. Topinard, Monsieur Joule (1890), Admirable Olry, Aimé Millet, Alphonse Karr, Amiral Aube, Céline Mantaland, Eugène Delaplanche, Gustave Flaubert, Heron (1891), Artemise, Auguste Hardy, De Quatrefages, Émile Bayard, Eugène Verconsin, Monsieur Alphard, Véra Sergine (1892), Albert Delpit, Bouquet, Carmen, Comte Leon Tolstoi, Lucie, Monsieur Hermite, Pasteur (1893), Adrien Marie, Capitaine Binger, Corne d'Abondance, Félix David, Félix Dubois, La Pompadour, Lieutenant Maritz, Lieutenant Mizon, Madame Moire, Marcel Monnier, Marcel Prevost (1894), Adrien Berger, Alexander Dumas (Alexandre Dumas), Lansdowne, Louis Figuier, Madame Carnot, Monsieur Gladstone, Président Burdeau, Triphylla Hybrida (1895), Alfred Rambaud, De Cherville, De Concourt, De Goncourt, Duc d'Aumale, Frère Orban, Garnier-Pagès, Gerbe de Corail, Miniature, Minos, Norma, Royal Purple (1896), Beaumarchais, Brutus, Corneilla, Florian, Molière, Monsieur Molier, Racine, Ronsard, Victor Hugo, Voltaire (1897), Alfred Fouillée, Colibri, Elsie Vert, Léo Delibes, Ministre Boucher, Monsieur Thibaut (1898), Comte Witte (a. k.a. Graf Witte), Alphand, Blanche de Castille, Caledonia, Carmen Sylva, Charles Garnier, Charles Samoureux, Colonel de Trentinian, Commandant Marchand, Dr. Foster, Général Gallieni, Monsieur Boucher, Nestor, Prince Georges, Sarah Bernhardt (1899), Charles Lamoureux, Madame Delina, Sculpteur Bartholomé, Statuaire Dalou (1900), Abbé Farges, Baron de Ketteler, Fleur Bleu, Général Voyron, Isabelle, Nautilus, Président Félix Faure, Stephen Pichon, Takou, Tien Tsin, Vincent d'Indy (1901), Dorothea Foubert, Dr. Behring, Frederick Passy, Héritage, Hugh Dutterail, Prix Nobel, Professeur Roentgen, Sully Prudhomme, Van t'Hoff (1902), Auguste Holmes, Émile Eskmann, Molesworth, Rochambeau, Rouget de l'Isle, Théroigne de Méricourt (1903), Armand Gautier, Émile Laurente, Le Robuste, Lucien Daniel, Pierre Mouillefert, Rhombifolia, Yves Delage (1904), Elfrida, Émile de Wildeman, Fascination, Fouvières, Henri Poincaré, John Lindsay, Leclerc du Sablon, Lecocq de Boisbaudram, Madame de Thèbes, Marcellin Berthelot, Naegeli, Phyrne, Pierre Bonnier, Rose Ballet Girl (1905), Alfred Picard, André Carnegie, Bertrade, Etienne Larny, Lucile Desmouling, Miarka, Monsieur Revoil (1906), Alfred Neymarck, Capitaine Tilho, Émile Lemoine, Émile Richebourg, Jules Daloges, Paul Meyer, Rose Porter (1907), Amiral Evans, Colonel Branlières, E. Joubert, Général d'Amade, Madame Eva Boye (Eva Boye), Susan Pasquier, Torpilleur, Voile Bleu (1908), Abbé David, André le Nostre, Juliette Adams, Lord Roberts, Paul Cambon, Professeur Lippman (1909), Émile Zola, Francois Boucher, Luc-Oliver Merson, Madame Thibault, Raoul Pugno (1910), Athènes, Calchas, Corinthe, Délos, Lacédémone, Messène, Sérervine (1911), Dollar Princess/Dollarprincessin, Dr. Bornet, Emma Calvé, Lucienne Bréval, Madame Lantelme, Rachilde (1912), Éliane, Fémina, L'Amoureuse, Madame du Gast, Madame Jacques Feuillet, Phoenix (Phénix), Rolla, Thaïs (1913), Firmin Gémier (1914).

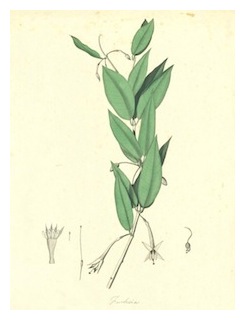

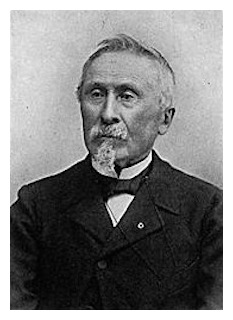

(Illustration: 1. Portrait of Lemoine; 2. Fuchsia 'Caledonia' 1899.)

Lenneana – Lennaeana; Named for Carl von Linné. F. lenneana (Warcz. 1852) is invalid and a synonym of F. boliviana (Carrière 1876) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Leptopoda – Having thin stalks. F. leptopoda (E.H.L.Krause 1905) is a synonym of F. denticulata (Ruiz & Pavón 1802) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Liana – A vine or plant with vine-like growth. Some fuchsias, such as F. regia for example, have a naturally lax and scrambling habit. In situations where there are other shrubs or trees competing for space and light, their elongated branches can often be found reaching over or through other shrubs or even far up into trees for several meters.

Liebman, Frederik (1813-1856) – Danish botanist. He studied botany at the University of Copenhagen, where he never obtained a degree, and subsequently went on study tours of Germany and Norway before becoming lecturer at the Danish Royal Veterinary and Agricultural College in 1837. In 1840 he travelled to Cuba and Mexico. On his return in 1845, he was appointed Professor of Botany at the University of Copenhagen and became the director of its botanical garden from 1852 until his death. F. liebmannii (H.Lév. 1912), named in his honor, is now a synonym of F. paniculata (Lindley 1856) in ➤ Section Schufia.

Liebmannii – Named in honor of Frederik Liebmann. F. liebmannii (H.Lév. 1912) is a synonym of F. paniculata (Lindley 1856) in ➤ Section Schufia.

Lilac Fuchsia – Common name occasionally applied to F. paniculata, or sometimes F. arborescens, both in ➤ Section Schufia, because of the resemblance of their inflorescences to those of lilacs (Syringa).

Lilja, Nils (1808-1870) – Swedish intellectual, writer, poet and botanist. Lilja's early education was at Malmö, where he excelled in botany and poetry. In 1828, Lilja went to study for the priesthood at the University of Lund but was set back in his studies by a lack of funds and hospitalization for an eye ailment. He later took up botany, geology, chemistry, literature, philosophy and political science on his own. A seemingly perennial student, he apparently spent fourteen years at university without ever obtaining the master's degree on which he was working, but often solicited the support of friends and admirers, including the crown prince of Sweden Oscar I, who provided scholarships and arranged fundraisers to help support his continuing efforts.

Lilja, Nils (1808-1870) – Swedish intellectual, writer, poet and botanist. Lilja's early education was at Malmö, where he excelled in botany and poetry. In 1828, Lilja went to study for the priesthood at the University of Lund but was set back in his studies by a lack of funds and hospitalization for an eye ailment. He later took up botany, geology, chemistry, literature, philosophy and political science on his own. A seemingly perennial student, he apparently spent fourteen years at university without ever obtaining the master's degree on which he was working, but often solicited the support of friends and admirers, including the crown prince of Sweden Oscar I, who provided scholarships and arranged fundraisers to help support his continuing efforts.

In 1838, he published the 524 page Skånes flora (Flora of Scania), a work that was not particularly well received by scientists at the time as it was completely written in Swedish, used the common vernacular names of plants and included much information on their folklore. It would be substantially reworked and republished in 1870. Among his numerous publications, Menniskan: Hennes uppkomst, hennes lif och hennes bestämmelse (Mankind: Its Origins, Life and Destiny; Stockholm, 1858) is considered to be his most significant and enduring effort. It was a long work covering various aspects of civilization, anthropology and natural history and was intended for a popular audience rather than academia.

Lilja's family life seemed to be as distracted as his myriad, eclectic professional interests: He was married three times, fathering fifteen children, and even found time to father at least four, or perhaps six, additional children with a maid. Reflecting his interest in botany, Lilja's offspring were sometimes given names inspired by plants. His unorthodox views on Christianity and social subjects such as free love, of course, earned him a certain amount of public scrutiny but his many friends and supporters remained personally faithful. In recognition of his efforts in the botanical sciences, Lilja was awarded an honorary PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1865.

At the beginning of the 1840's Lilja tried his hand at the taxonomy of a number of Central American fuchsias, quartered in today's Ellobium and Encliandra sections, establishing new genera for them: Ellobium fulgens (DC, Lilja 1841), Spachia fulgens (DC, Lilja 1840) and Myrinia microphylla (Lilja 1840).

There is no explanation preserved in his publications as to the reason for his sudden interest in these fuchsia species. However, Myrinia appears in the Första Supplementet (1840) of Lilja's Flora öfver Sveriges odlade vexter, (Flora of Sweden's Cultivated Plants,1839), a gardening book that sorted the plants along the Linnaean system and offered practical advice to Swedes on growing local and exotic plants. The book's full title continues, "innefattande de flesta på fritt land odlade vexter i Sverige, jemte de allmännare och vackrare fenstervexterna…" (including most of the outdoor plants in Sweden, along with the more general and beautiful indoor plants…) so his motivation was perhaps the rising fashionableness of fuchsias in Europe. Lilja's taxonomic efforts on behalf of Fuchsia, though, are now all synonymous with the names by which they are known today, F. fulgens and F. microphylla.

Not giving up easily, Lilja also published the Fuchsiaceae family in the second edition of his Skånes flora (1870) to house his genera but that family is also invalid: Fuchsia belongs to the ➤ Onagraceae, or Evening Primrose Family.

(Illustration: Portrait of Nils Lilja.)

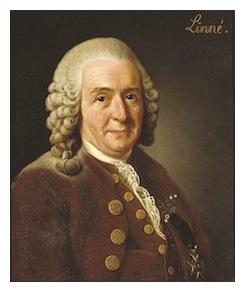

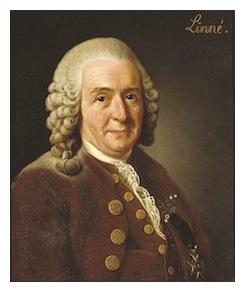

Linnaeus, Carl (1707-1778) – Swedish botanist, physician and zoologist who laid the foundation of botanical nomenclature in modern science starting with his Species Plantarum (1753). It was Linnaeus who shortened Charles Plumier's long descriptive name for the first fuchsia from Fuchsia triphylla, flora coccineo in accordance with the binomial nature of the nomen triviale, or trivial

Linnaeus, Carl (1707-1778) – Swedish botanist, physician and zoologist who laid the foundation of botanical nomenclature in modern science starting with his Species Plantarum (1753). It was Linnaeus who shortened Charles Plumier's long descriptive name for the first fuchsia from Fuchsia triphylla, flora coccineo in accordance with the binomial nature of the nomen triviale, or trivial names, he assigned to make his classified species easier to remember and identify. Linnæus was ennobled by the Swedish king in 1757 for his scientific achievements and took the name Carl von Linné. His name is also rendered as Carolus Linnaeus in Latin publications. Daniel Solander, who journeyed with Joseph Banks on the famous voyage of discovery of the HMS Endeavor, was his botany student at the University of Uppsala and one of his numerous "apostles."

names, he assigned to make his classified species easier to remember and identify. Linnæus was ennobled by the Swedish king in 1757 for his scientific achievements and took the name Carl von Linné. His name is also rendered as Carolus Linnaeus in Latin publications. Daniel Solander, who journeyed with Joseph Banks on the famous voyage of discovery of the HMS Endeavor, was his botany student at the University of Uppsala and one of his numerous "apostles."

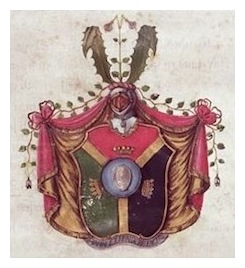

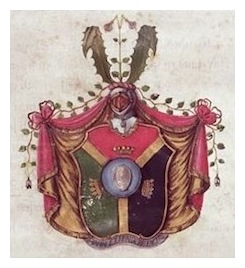

(Ilustrations: 1.Portrait of Carl von Linné, Alexander Roslin, 1775; 2. Linné's coat of arms features a field divided into his three kingdoms of animal (Rouge), plant (Vert) and mineral (Sable). The crest is the twinflower, or Linnæa borealis, his favorite plant and personal badge.)

Llewelynii – Named in honor of the Welsh-born botanist, Llewelyn Williams (1901-1980). See ➤ Williams/a>; F. llewelynii (J.F.MacBride 1941) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Loja Province, Ecuador – Considered by botanists to be a "hotbed of speciation in Fuchsia," the upper elevation cloud forests of Loja Province in southern Ecuador are the only home of no less than five species in the F. loxensis species group of Fuchsia section Fuchsia. These even include a new species, only recently discovered in 1995 and described as F. aquaviridis. The other four species endemic to the region are F. campii, F. scherffiana, F. steyermarkii and F. summa. Considering that studies and collections of new plants coming from southern Ecuador have increased dramatically in the past few years, it is not inconceivable that additional new fuchsias might be forthcoming from this botanically fascinating region. Unfortunately, many uncommon plants in Loja Province, including the new F. aquaviridis, are also increasingly being endangered by roads and land clearings. (Illustration: Coat of Arms of Loja Provice. Note the quasi-mantling rendered as green foliage.)

Loja Province, Ecuador – Considered by botanists to be a "hotbed of speciation in Fuchsia," the upper elevation cloud forests of Loja Province in southern Ecuador are the only home of no less than five species in the F. loxensis species group of Fuchsia section Fuchsia. These even include a new species, only recently discovered in 1995 and described as F. aquaviridis. The other four species endemic to the region are F. campii, F. scherffiana, F. steyermarkii and F. summa. Considering that studies and collections of new plants coming from southern Ecuador have increased dramatically in the past few years, it is not inconceivable that additional new fuchsias might be forthcoming from this botanically fascinating region. Unfortunately, many uncommon plants in Loja Province, including the new F. aquaviridis, are also increasingly being endangered by roads and land clearings. (Illustration: Coat of Arms of Loja Provice. Note the quasi-mantling rendered as green foliage.)

Longiflora – Having a long flower. F. longiflora (Bentham 1845) is a synonym of F. macrostigma (Bentham 1844) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Loxensis – From Loja Province, Ecuador. See F. loxensis in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Ludwigia – A sister genus to Fuchsia in the ➤ Onagraceae family currently composed of about seventy-six species. Ludwigia L. are cosmopolitan in distribution and generally found in wet or swampy habitats, mainly in tropical regions. The genus is considered the basal genus of the family and is the only member in its subfamily, Ludwigioideae (see also). The genus was named for the German botanist, Christian Gottlieb Ludwig (1709-1773), who was apparently not exactly pleased by the swampy honor Linnaeus bestowed on him.

Ludwigia – A sister genus to Fuchsia in the ➤ Onagraceae family currently composed of about seventy-six species. Ludwigia L. are cosmopolitan in distribution and generally found in wet or swampy habitats, mainly in tropical regions. The genus is considered the basal genus of the family and is the only member in its subfamily, Ludwigioideae (see also). The genus was named for the German botanist, Christian Gottlieb Ludwig (1709-1773), who was apparently not exactly pleased by the swampy honor Linnaeus bestowed on him.

(Illustration: Ludwigia sedoides, the mosaic plant.)

Ludwigioideae – One of two subfamilies in the ➤ Onagraceae, or Evening Primrose family (see also). Fuchsia is a member species of its other subfamily, Onagroideae .

Lyell, Sir Charles (1795-1875) – British lawyer and the leading geologist of his time. Lyell was a close friend and correspondant of both Charles Darwin and James Hooker (see both also). He is best known for his three-volume Principles of Geology (1830-1833), which popularized the idea that the earth was shaped by the same processes still in operation today. It was in a letter to Lyell in 1866 that Darwin reveals his new awareness of "Fuchsia, etc" and other temperate plants found in the Organ Mountains of south-eastern Brazil and separated from relatives in the Andes Mountains across "low intervening hot countries." See ➤ Darwin; ➤ Hooker.

Lycioides – Resembling Lycium afrum, the thorny boxwood, from a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family, the Solanaceae. See F. lycioides in ➤ Section Kierschlegeria.

Lyciopsis – Resembling, or appearing like, a Lycium, a genus of often boxwood-like flowering plants in the nightshade family, the Solanaceae. Lyciopsis thymifolia (Kunth) Spach 1835 is a synonym of Fuchsia thymifolia subsp. thymifolia ➤ Section Encliandra. The member of the spurge family, Lyciopsis cuneata (Vahl) Schweinf. 1867, is a synonym of Euphorbia cuneata Vahl. See also ➤ Lycioides.

This name is a synonym of Euphorbia cuneata Vahl.

The record derives from WCSP which reports it as a synonym (record 335098) with original publication details: Beitr. Fl. Aethiop. 37 1867.

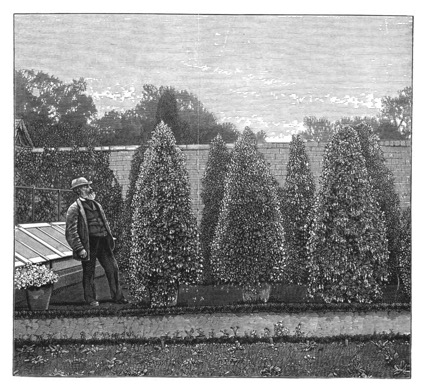

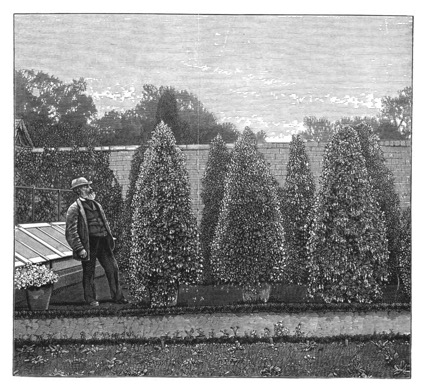

Lye, James (1830-1906) – Victorian gardener and prolific fuchsia hybridizer who was responsible for introducing over ninety cultivars from about 1860 to 1897. Many of his efforts still exist and are still popular today. A particular hallmark of his crosses was often a waxy white calyx. Lye was the head gardener at Clyffe Hall in Market Lavington, England until he retired 1896 and was noted for the skill with which he grew large pyramids there. Some of his creations reached impressive sizes of ten feet tall and four feet wide. His numerous hybrids, many of which are still grown today, include Clipper, Beauty of Wiltshire, James Lye, Letty Lye, Betty Lye, Mrs. Lye, Mrs. J. Bright, Mrs. Huntley, James Huntley, Charming, Elegance, Beauty of Swanley and Mrs. F. Glass. Lye also bred potatoes.

Lye, James (1830-1906) – Victorian gardener and prolific fuchsia hybridizer who was responsible for introducing over ninety cultivars from about 1860 to 1897. Many of his efforts still exist and are still popular today. A particular hallmark of his crosses was often a waxy white calyx. Lye was the head gardener at Clyffe Hall in Market Lavington, England until he retired 1896 and was noted for the skill with which he grew large pyramids there. Some of his creations reached impressive sizes of ten feet tall and four feet wide. His numerous hybrids, many of which are still grown today, include Clipper, Beauty of Wiltshire, James Lye, Letty Lye, Betty Lye, Mrs. Lye, Mrs. J. Bright, Mrs. Huntley, James Huntley, Charming, Elegance, Beauty of Swanley and Mrs. F. Glass. Lye also bred potatoes.

(Illustration: Lye stands looking at a virtual forest of his fuchsia pyramids. From his obituary in the Gardener's Chronicle, Vol. XXIX, 3rd Series, January-June 1906, p 94. Feb 10, 1906.)

M919 Fuchsia – A tripartite-class mine-hunting vessel formerly belonging to the Belgian Navy. The vessel was commissioned in 1988. The M919 Fuchsia's botanically inspired sister ships in its class were the Dianthus, Iris and Myosotis. Sold to France in 1993, the M919 Fuchsia is now called the M652 Céphée.

(Illustration: See M919 Fuchsia at ➤ ShipSpotting.com © G. Gyssels.)

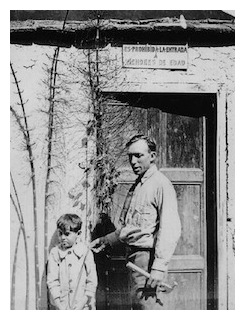

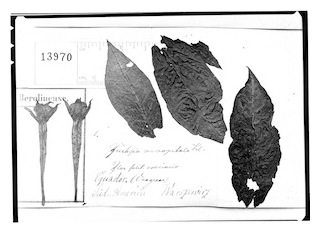

Macbride, James Francis (1892-1976) – American botanist and plant hunter. In 1921, he joined the Field Museum of Chicago to head its newly created Flora of Peru project and traveled to Peru on expedition in 1922, and again in 1923, to collect almost 6,000 specimens. Among the seven fuchsia specimens with which he returned were actually two that proved new to science: F. abrupta (Johnston 1925) and F. ferreyae (Berry 1980), which had originally been wrongly identified as F. decussata (Ruiz & Pavon). Beginning in 1929, Macbride spent ten years traveling across Europe to photograph over 40,000 type and other historically important specimens at all major herbaria. Aside from their usefulness to botanists in North America, his photographs would prove to be of immense value after the destruction and losses suffered by a number of herbaria during World War II.

Macbride, James Francis (1892-1976) – American botanist and plant hunter. In 1921, he joined the Field Museum of Chicago to head its newly created Flora of Peru project and traveled to Peru on expedition in 1922, and again in 1923, to collect almost 6,000 specimens. Among the seven fuchsia specimens with which he returned were actually two that proved new to science: F. abrupta (Johnston 1925) and F. ferreyae (Berry 1980), which had originally been wrongly identified as F. decussata (Ruiz & Pavon). Beginning in 1929, Macbride spent ten years traveling across Europe to photograph over 40,000 type and other historically important specimens at all major herbaria. Aside from their usefulness to botanists in North America, his photographs would prove to be of immense value after the destruction and losses suffered by a number of herbaria during World War II.

During his absence, the Field Museum continued to acquire Peruvian collections from various sources such as Ellsworth Killip, Guillermo Klug, Francis Pennell, Albert Smith, Agusto Weberbauer, Llewelyn Williams and others. By 1936, the Field herbarium contained over 33,000 Peruvian specimens, the largest collection of its kind anywhere, and the Flora of Peru series was launched with the publication of Volume 13, Number 1. Over the next twenty-five years nearly 180 plant families were to be published in the series, of which Macbride personally treated 150. Fuchsia would be covered in Part 4, No. 1 where Macbride himself described seven new fuchsia species all named in honor of various deserving people: F. aslundii, aspazui, fischerii, llewelynii, munzii, osgoodii and woytkowskii (see each also.) Unfortunately, all would later turn out to be synonymous with previously established species. In the late 1940s, Macbride moved to California but continued his work using the facilities of the University of California and Stanford University. His last families were published in 1960, with only twenty left undone by the time he died.

Over the next twenty-five years nearly 180 plant families were to be published in the series, of which Macbride personally treated 150. Fuchsia would be covered in Part 4, No. 1 where Macbride himself described seven new fuchsia species all named in honor of various deserving people: F. aslundii, aspazui, fischerii, llewelynii, munzii, osgoodii and woytkowskii (see each also.) Unfortunately, all would later turn out to be synonymous with previously established species. In the late 1940s, Macbride moved to California but continued his work using the facilities of the University of California and Stanford University. His last families were published in 1960, with only twenty left undone by the time he died.

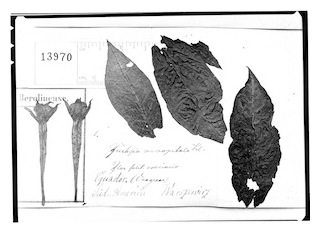

(Illustrations: 1. Detail of MacBride posed with a giant Equisetum and small boy at Huánuco on the Field Museum expedition to Peru in April, 1922, Field Museum Neg. 47288; 2. F. macropetala type from the Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum in Berlin-Dahlem. Almost its entire collection of botanical specimens, some dating back three hundred years, as well as the library, was tragically lost in a bomb attack and fire on March 1, 1943. This type, however, was preserved in Macbride's photography.)

Macrantha – Large flowered. F. macrantha (Hooker 1846) is a synonym of F. apetala (Ruiz & Pavón 1802) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Macrophylla – Having large leaves. See F. macrophylla (I.M.Johns. 1925) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Macropetala – Having large petals. See F. macropetala (J. Presl. 1831) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Macrostemma – Having a large stemma, or garland or crown. F. macrostemma (Ruiz & Pavón 1802) is a synonym of F. magellanica (Lamarck 1788) in ➤ Section Quelusia, as are F. macrostemma var. conica (Lindl., Sweet 1833), F. macrostemma var. globosa (Lindl., Sweet 1833), F. macrostemma var. gracilis (Lindl., Sweet 1833), F. macrostemma var. grandiflora (Hook. & Arn. 1833), F. macrostemma var. parviflora (Hook. & Arn. 1833), F. macrostemma var. recurvata (Hook. 1836) and F. macrostemma var. tenella (Lindl., DC. 1828).

Macrostigma – Having a large stigma (see also). See F. macrostigma (Bentham 1844) in ➤ Section Fuchsia. F. macrostigma var. longiflora (Benth., Munz 1943) is a synonym.

Magdalenae – From the Magdalena Department in Colombia. See F. magdalenae (Munz 1943) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Magellanica – From the Magellanic region, or Straights of Magellan. See F. magellanica (Lamarck 1788) in ➤ Section Quelusia. No subspecies, varieties or forms are currently recognized.

Magellanica – From the Magellanic region, or Straights of Magellan. See F. magellanica (Lamarck 1788) in ➤ Section Quelusia. No subspecies, varieties or forms are currently recognized.

This species has collected numerous invalid synonyms: Dorvalia eucharis (Comm. ex Lam. 1788); F. araucana (F.Phil. 1876); F. chonotica (Phil. 1856); F. coccinea var. chonotica (Phil., Reiche 1897); F. coccinea var. macrostema (Ruiz & Pavón, Hook. 1847); F. coccinea var. macrostemma (Ruiz & Pavón, Hook.f. 1847); F. coccinea var. robustior (Hook.f. 1847); F. conica (Lindl. 1827); F. decussata (Graham 1824) [Illegitimate]; F. discolor (Lindl. 1836); F. globosa (Lindl. 1836); F. gracilis (Lindl. 1836); F. gracilis var. macrostemma (Ruiz & Pavón, Lindl. 1827); F. gracilis var. multiflora (Lindl. 1827); F. gracilis var. tenella (Lindl. 1827); F. macrostema var. grandiflora (Hook. 1833); F. macrostemma var. conica (Lindl., Sweet 1833); F. macrostemma var. globosa (Lindl., Sweet 1833); F. macrostemma var. gracilis (Lindl., Sweet 1833); F. macrostemma var. grandiflora (Hook. & Arn. 1833); F. macrostemma var. parviflora (Hook. & Arn. 1833); F. macrostemma var. recurvata (Hook. 1836); F. macrostemma var. tenella (Lindl., DC. 1828); F. magellanica var. alba (Clarence Elliott 1932); F. magellanica var. conica (Lindl., L.H.Bailey 1900); F. magellanica var. discolor (Lindl. L.H.Bailey 1900); F .magellanica var. eburnea (Pisano 1979); F. magellanica var. globosa (Lindl., L.H.Bailey 1900); F. magellanica var. gracilis (Lindl., L.H.Bailey 1900); F. magellanica var. macrostemma (Ruiz & Pav., Munz 1943); F. magellanica var. molinae (Espinosa 1929); F. magellanica var. riccartonii (Tillery, L.H.Bailey 1915); F. multiflora (L. 1774); F. myrtifolia (Koehne 1893); F. pumila (Voss, Voss 1894); F. pumila (Meun. 1926); F. recurvata (Niven ex Hook. 1836); F. riccartonii (Tillery 1871); F. tenella (Lindl., G.Don 1830); F. thompsonii (Koehne 1893); F. virgata (Sweet ex Jacques 1834), Nahusia coccinea (Schneevoogt 1792) and Thilcum tinctorium (Molina 1810).

Magellanica hybrids, or Magellanicas – A group of winter-hardy garden hybrids closely resembling the southern Chilean and Argentinian species, Fuchsia magellanica in the ➤ Quelusia section of the genus, from which they were developed. Frequently cultivated outdoors in gardens throughout the world, magellanicas are often also found naturalized in many climatically favorable areas, such as the British Isles, for example, or coastal France. In Ireland, especially, magellanicas have become so widespread in the countryside that they seem to have reached almost iconic status for that country alongside the shamrock.

Magellanica hybrids, or Magellanicas – A group of winter-hardy garden hybrids closely resembling the southern Chilean and Argentinian species, Fuchsia magellanica in the ➤ Quelusia section of the genus, from which they were developed. Frequently cultivated outdoors in gardens throughout the world, magellanicas are often also found naturalized in many climatically favorable areas, such as the British Isles, for example, or coastal France. In Ireland, especially, magellanicas have become so widespread in the countryside that they seem to have reached almost iconic status for that country alongside the shamrock.

Mostly of early and unknown horticultural origin, the group includes many well-known and attractive cultivars or garden selections such as ''Alba,' Aurea,' 'Conica,' 'Exonensis,' 'Globosa,' 'Gracilis,' 'Macrostema,' 'Molinae,' 'Pumila,' 'Riccartonii,' 'Tricolor,' 'Variegata,' 'Versicolor' and a number of others. Despite common misconceptions to the contrary, current and past, recent pollen-stain tests conducted on specimens of this group of plants have confirmed that all are of hybrid origin of varying degrees, possibly resulting from early uncontrolled or accidental crosses with another close relative in Section Quelusia, F. coccinea.

Confusingly, the true F. magellanica is also widely and evenly variable throughout the whole of its extensive range. Botanists, therefore, currently recognize no naturally occurring subspecies or varieties within the species. Only the verified species itself should be called F. magellanica and care must be taken not to assume scientific status for any of the magellanica-like garden plants. Or even for new selections from the wild. For example, F. magellanica var. macrostema is inaccurate and invalid in scientific nomenclature and should not be used. A correct botanical convention to follow for its name would be F. x magellanica 'Macrostema,' to indicate its status and origin as a garden selection or hybrid.

(Illustration: A hardy magellanica-hybrid selection planted out at the Lake Wilderness Botanical Garden in the Pacific Northwest of the US.)

Magenta – Trade name for the synthetic analine dye, rosaniline hydrochloride. The name was invented in 1859 by Edward Chambers Nicholson after the Battle of Magenta fought that year and is a synonym of another trade name, fuchsine, also coined that same year by Renard Frères et Franc in France. See ➤ Fuchsine; ➤ The Color Fuchsia.

Magniflora – Having large flowers. F. × magniflora (B.S.Williams 1855) is an unresolved name.

Mapuche – The indigenous peoples of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. The ethnicity includes sub-groups such as the Picunche (people of the north) and the Huilliche (people of the South) who shared a common social, religious and economic structure, as well as a linguistic heritage. The Mapuche knew F. magellanica as chilco (see also) and used it as a black dye for cloth and for medicinal purposes.

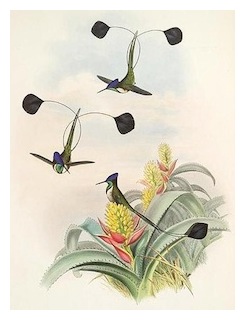

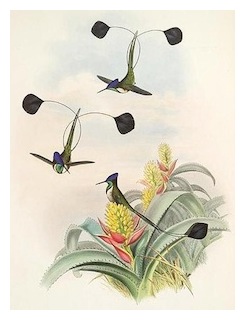

Mathews, Andrew (1801-1841) – His name is sometimes recorded as Andrew Matthews, Alexander Matthews or Andrés Mateus. Mathews was a British naturalist and member of the Linnean Society who left England to collect in South America. He came first to Chile but eventually settled in Peru where he married a local woman. Between 1830 and 1841, Mathews was mainly active in Peru, Brazil and Chile/ He also undertook a journey to Polynesia to collect on the islands of French Polynesia and others, such as the Pitcairn Islands and the Friendly Islands (Tonga). Described by a contemporary as a "traveling collector of natural objects," he acquired numerous birds, insects and plants and was even commended by an acquaintance to Charles Darwin during his stop in Peru in 1834. The two were unfortunately not destined to meet as Mathews had already set out on a trip across the Andes to the Rio de la Plata. His eager clients included the celebrated nurseryman George Loddiges (1786-1846), to whom he sent exotic plants and birds, such as the rare marvelous spatuletail hummingbird, which would be named Loddigesia mirabilis, and Sir William Hooker, the well-connected botanist and director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Mathews died at Chachapoyas in the Amazonas Province of Peru in 1841 after a period of declining health.

Mathews, Andrew (1801-1841) – His name is sometimes recorded as Andrew Matthews, Alexander Matthews or Andrés Mateus. Mathews was a British naturalist and member of the Linnean Society who left England to collect in South America. He came first to Chile but eventually settled in Peru where he married a local woman. Between 1830 and 1841, Mathews was mainly active in Peru, Brazil and Chile/ He also undertook a journey to Polynesia to collect on the islands of French Polynesia and others, such as the Pitcairn Islands and the Friendly Islands (Tonga). Described by a contemporary as a "traveling collector of natural objects," he acquired numerous birds, insects and plants and was even commended by an acquaintance to Charles Darwin during his stop in Peru in 1834. The two were unfortunately not destined to meet as Mathews had already set out on a trip across the Andes to the Rio de la Plata. His eager clients included the celebrated nurseryman George Loddiges (1786-1846), to whom he sent exotic plants and birds, such as the rare marvelous spatuletail hummingbird, which would be named Loddigesia mirabilis, and Sir William Hooker, the well-connected botanist and director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Mathews died at Chachapoyas in the Amazonas Province of Peru in 1841 after a period of declining health.

Among the many finds made by Mathews was a new fuchsia collected in the Chachapoyas area, probably sometime between 1835 and 1840. For over a hundred years, however, this original type specimen apparently languished, unnumbered, in the colossal herbarium (herbaria is probably more accurate) of the botanical garden in Geneva, Switzerland. Better late than never, J. Francis MacBride (see also), of the Field Museum of Chicago, eventually recognized that the Mathews specimen preserved at Geneva was a distinct species. He published it as F. mathewsii, first in Candollea (8:24) in 1940 and then again included it in his immense Flora of Peru (8: 4: 1) in 1941. Perhaps partially explaining why it languished so long, F. mathewsii seems also to have been easily confused in herbarium specimens. Indeed, MacBride himself published another collection of the same fuchsia made in 1906 by August (Agusto) Weberbauer (1871-1948) as F. fischeri, in the same volume of the Flora of Peru as F. mathewsii. A further collection made by Harvey E. Stork (1890-1959) in 1938 would be published by Phillip A. Munz as F. storkii in 1943.

Among the many finds made by Mathews was a new fuchsia collected in the Chachapoyas area, probably sometime between 1835 and 1840. For over a hundred years, however, this original type specimen apparently languished, unnumbered, in the colossal herbarium (herbaria is probably more accurate) of the botanical garden in Geneva, Switzerland. Better late than never, J. Francis MacBride (see also), of the Field Museum of Chicago, eventually recognized that the Mathews specimen preserved at Geneva was a distinct species. He published it as F. mathewsii, first in Candollea (8:24) in 1940 and then again included it in his immense Flora of Peru (8: 4: 1) in 1941. Perhaps partially explaining why it languished so long, F. mathewsii seems also to have been easily confused in herbarium specimens. Indeed, MacBride himself published another collection of the same fuchsia made in 1906 by August (Agusto) Weberbauer (1871-1948) as F. fischeri, in the same volume of the Flora of Peru as F. mathewsii. A further collection made by Harvey E. Stork (1890-1959) in 1938 would be published by Phillip A. Munz as F. storkii in 1943.

However, it's unclear why the great gap of a hundred years between collection and description. The plant itself is not especially rare, being a common and scattered, or even a locally frequent, shrub in its native range. Perhaps it was just caught in the gold rush of South America's botanical riches that started at the beginning of the 19th Century. So many new plants were being passed too rapidly for herbaria first in Europe, and later in the United States as well, to easily digest. In fact, many new plants, fuchsias included, are still regularly being uncovered in the diverse and rich ecosystems of South America. Or hidden away in herbaria/ Part of the problem of recognition might also have been that Mathews' valuable collections are quite dispersed and no complete set exists anywhere.

However, it's unclear why the great gap of a hundred years between collection and description. The plant itself is not especially rare, being a common and scattered, or even a locally frequent, shrub in its native range. Perhaps it was just caught in the gold rush of South America's botanical riches that started at the beginning of the 19th Century. So many new plants were being passed too rapidly for herbaria first in Europe, and later in the United States as well, to easily digest. In fact, many new plants, fuchsias included, are still regularly being uncovered in the diverse and rich ecosystems of South America. Or hidden away in herbaria/ Part of the problem of recognition might also have been that Mathews' valuable collections are quite dispersed and no complete set exists anywhere.

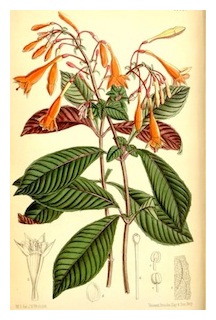

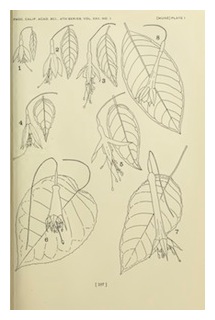

In addition to F. mathewsii, MacBride actually found two further new fuchsias collected by Mathews a hundred years earlier, which had long been in hiding, undescribed, in Geneva as well: F. fontinalis and F. rivularis. Astonishingly, yet two more novel fuchsias collected by Mathews went to the botanical garden at Oxford, but these had had a more timely description by Fielding & Gardener already in 1844: F. confertifolia and F. pilosa. In all, Mathews was responsible for the discovery and collection of five new species of fuchsia. It's worth wondering if Mathews' additional focus on birds, especially on hummingbirds for George Loddiges, helped draw his attention to the fuchsias which many hummingbirds frequently visit to feed. All in all, five new fuchsias is certainly a testament to Mathews' skill and his discerning eye as other collectors would later pass near areas in which Mathews collected in the intervening century to MacBride without noticing the fuchsias. See F. mathewsii in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

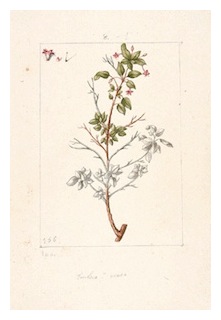

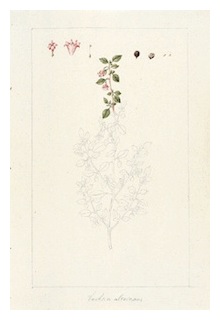

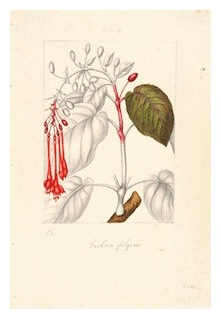

(Illustrations: 1. The rare and now-endangered Marvelous Spatuletail was discovered by Mathews in 1835 at the forest edges of the Río Utcubamba area in Amazonas and subsequently described from the skin of a mature male sent to England. John Gould, author, and H.C. Richter, illustrator, A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-Birds, 1880, plate 161; 2. F. pilosa and 3. F. confertifolia, H. B. Fielding, Sertum Plantarum (1844), Tables 27 & 28.

Mathewsii – Named in honor of Andrew Mathews (1801-1841). See: F. mathewsii (J.F.McBride 1940) in ➤ Section Fuchsia; ➤ Mathews.

Mattoana – From an area covered by mato, also spelled matto, or thick brush or bushes. The Mato Grosso (also Matto-Grosso) is a state in Western Brazil bordering Bolivia and means, literally, "thick bushes". The southwest part of the state was ceded to Bolivia in 1903. F. mattoana (E.H.L.Krause 1906) is a synonym of F. tunariensis (Kuntze 1898) in ➤ Section Hemsleyella.

Maya – As did most probably their ancient ancestors, the modern Maya recognize and make use of several species of Fuchsia native to the areas they inhabit in Southern Mexico and Central America. Women of the Tzotzil-speaking Zinacantec Maya in the highlands of Chiapas State, Mexico, for example, add young tips of yich'ak mut or "bird's claw" (Fuchsia paniculata) to the ingredients of a ritual "flower water" brew with which they bathe their newborn babies. As ba ikatzil or "top load", Fuchsia paniculata is eaten by sheep. Leaves of Leandra subseriata, Miconia guatemalensis and M. mexicana are boiled with fuchsia dye to produce a red color used for sashes. Plants of Fuchsia microphylla ssp. quercetorum, called Fuczajal ch'ulelal nichim or the "red ghost flower" (also ch'ix tzib, kampana pox, natz'il te', tzajal pom tz'unun te', or ventex chij) are sold in Tuxtla markets at Christmas time. The shrub is a common element in the understory of the temperate pine-oak and evergreen cloud forest around highland hamlets and villages. (For more information on the full ethnobotany of the Zinacatec Maya, see Dennis E. Breedlove and Robert M. Laughlin, The Flowering of Man: A Tzotzil Botany of Zinacantán, Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, No. 35, 1993, 2 Vols.)

Membranacea – Membrane-like, skin-like. See F. membranacea (Hemsley 18976) in ➤ Section Hemsleyella.

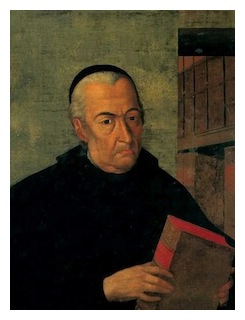

Mendel, Gregor (1822-1884) – Austrian scientist and Augustinian friar who founded the science of genetics by demonstrating inheritance patterns in peas. Mendel did his work at the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brünn in Austro-Hungarian Moravia (today Brno, Czech Republic). He had originally entered religious life there in 1843 to train for the priesthood but left to pursue studies at the University of Vienna. He returned to the Abbey as a teacher in 1854 and became abbot in 1867. Most of Mendel's published work was on meteorology and it was only in the early 20th century that his seminal work on peas (Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden, 1866)

Mendel, Gregor (1822-1884) – Austrian scientist and Augustinian friar who founded the science of genetics by demonstrating inheritance patterns in peas. Mendel did his work at the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brünn in Austro-Hungarian Moravia (today Brno, Czech Republic). He had originally entered religious life there in 1843 to train for the priesthood but left to pursue studies at the University of Vienna. He returned to the Abbey as a teacher in 1854 and became abbot in 1867. Most of Mendel's published work was on meteorology and it was only in the early 20th century that his seminal work on peas (Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden, 1866) was rediscovered and he began to be hailed as the Father of Genetics.

was rediscovered and he began to be hailed as the Father of Genetics.

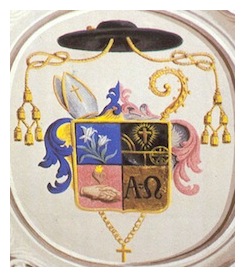

Mendel was also very fond of fuchsias and he grew and bred them in the garden at his monastery. In an early group photo of the friars at the abbey taken sometime after 1860, he distinctly poses himself examining a fuchsia. One might imagine it to have been one of his own garden crosses, he so closely and intently studies the pale, single blossom and buds dangling from the small sprig held in his hand. In fact, it's not even the only photo in which Mendel poses himself with what is obviously a favorite flower. Fuchsias weren't, however, involved in his genetic studies. Mendel is often said to have incorporated a fuchsia into his coat of arms but a close examination of his abbotical shield, at least, painted on a plaster cartouche on the ceiling of the library at the Abbey of St. Thomas reveal what appear to be naturalistically styled lilies in the first quarter.

(Illustrations: Mendel examines a fuchsia; Mendel's coat of arms as Abbot of St. Thomas.)

Meridensis – From the state of Médrida in Venezuela. F. meridensis (Steyermark 1952) is a synonym of F. venusta (Kunthe 1823) in ➤ Section Fuchsia.

Meristem – The plant tissue that allows growth. It is composed of totipotent cells which have the ability to differentiate when dividing.

Mexiae – Named in honor of Ynés Mexía. F. mexiae (Munz 1943) is a synonym of F. parviflora (Lindley 1838) in ➤ Section Encliandra. [F. parviflora (Lindley 1827) is a synonym of F. encliandra (Zucc. 1837).] See Bracelin.

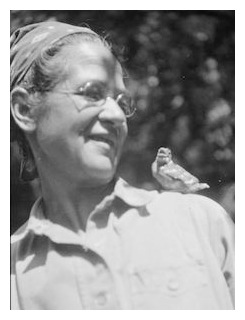

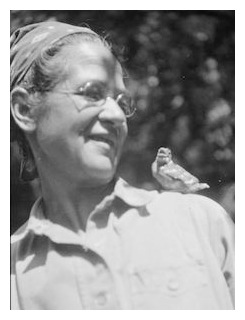

Mexía, Ynés (1870-1938) – Mexican-American botanist who collected primarily in Mexico and Central and South America. The daughter of Enrique Mexía, a Mexican diplomat in Washington, DC and Sarah Wilmer, from an old established family in Maryland, Ynés Mexía worked her way through two marriages and a nervous breakdown before moving to San Francisco and embarking on a career in botany at the age of fifty-five. After a stint as a social worker and formative involvement with the Sierra Club, she entered the University of California at Berkeley to study botany in 1921 but never finished her degree. A prolific collector and colorful character, she was perhaps ultimately most interest in the hunt and adventure of the field rather than the academic organization of her many specimens before she was away in search of more. Indominitable, and reputedly a bit fractious with others on expeditions, Mexía was at her best when she set off on her own. On one trip, she traveled the length of the Amazon River to the Andes with a guide and three men in a canoe, and then spent three months living with the Araguarunas, an Amazonian tribe. Ultimately her field collections amounted to an astonishing 33,000 specimens and were to be catalogued and distributed to institutions around the would only with the assistance of her friend, ➤ Nina Floy Bracelin, at the University of California at Berkeley Mexía was also close friends with the distinguished and formidable botanist at the California Academy of Sciences, Alice Eastwood, who would continue to employ Bracelin to catalogue Mexía's collections from a bequest after her death. Her collection of Fuchsia mexiae was named in her honor by Phillip K. Munz in 1943 but ultimately proved to be to be a synonym of F. parviflora (Lindley 1838).

Mexía, Ynés (1870-1938) – Mexican-American botanist who collected primarily in Mexico and Central and South America. The daughter of Enrique Mexía, a Mexican diplomat in Washington, DC and Sarah Wilmer, from an old established family in Maryland, Ynés Mexía worked her way through two marriages and a nervous breakdown before moving to San Francisco and embarking on a career in botany at the age of fifty-five. After a stint as a social worker and formative involvement with the Sierra Club, she entered the University of California at Berkeley to study botany in 1921 but never finished her degree. A prolific collector and colorful character, she was perhaps ultimately most interest in the hunt and adventure of the field rather than the academic organization of her many specimens before she was away in search of more. Indominitable, and reputedly a bit fractious with others on expeditions, Mexía was at her best when she set off on her own. On one trip, she traveled the length of the Amazon River to the Andes with a guide and three men in a canoe, and then spent three months living with the Araguarunas, an Amazonian tribe. Ultimately her field collections amounted to an astonishing 33,000 specimens and were to be catalogued and distributed to institutions around the would only with the assistance of her friend, ➤ Nina Floy Bracelin, at the University of California at Berkeley Mexía was also close friends with the distinguished and formidable botanist at the California Academy of Sciences, Alice Eastwood, who would continue to employ Bracelin to catalogue Mexía's collections from a bequest after her death. Her collection of Fuchsia mexiae was named in her honor by Phillip K. Munz in 1943 but ultimately proved to be to be a synonym of F. parviflora (Lindley 1838).

(Illustration: Detail of ➤ Ynés Mexía with a young black-headed grosbeak about 1921. From the archives at the California Academy of Sciences.)

Meza Rodríguez de Hurtado, Irene Témpora. – Peruvian botanst. As I. Meza, she is credited with the collection of the rare Fuchsia mezae (see also below) in Peru in 1965. The new species was described in his or her honor from the specimen housed at the Missouri Botanical Garden's herbarium only in 1999. Meza is also listed as the collector of numerous other botanical accessions in the herbarium of the University of San Marcos in Lima taken during the directorship of Ramón Ferreyra Huerta (1910-2005), as well as those at the Missouri Botanical Garden. Meza went on the earn a doctorate. See F. mezae in ➤ Section Hemsleyella.

Mezae – Named in honor of Irene Témpora Meza Rodríguez de Hurtado, a Peruvian botanist. In 1965, Meza made a single collection of this apparently very rare fuchsia at a single location: “Péru. Huanuco: Quebrada antes de Utao, 2430 m, 4 Oct 1965”, when she was a student in Systemic Botany at the University of San Marcos in Lima. A specimen from this collection was sent to the Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) where it remained unrecognized (as Meza 360) until described as a new species in Meza's honor only in 1999. Meza is responsible for numerous other collections that entered the herbarium of the University of San Marcos in Lima (USM) taken during the directorship of Ramón Ferreyra Huerta (1910-2005). A number of these are duplicated at the Missouri Botanical Garden as well. One or more other collections of F. mezae are at the San Marcos herbarium as well. See F. mezae (P.E.Berry & Hermsen 1999) in ➤ Section Hemsleyella; Meza.

Michoacanensis – From the state of Michoacán de Ocampo in Mexico. Fuchsia michoacanensis (Sessé & Moçino 1888) is a synonym of Fuchsia parviflora (Lindley 1827).

Microphylla – Having small leaves. See. F. microphylla in ➤ Section Encliandra, of which there are six subspecies.

Microphylloides – Resembling F. microphylla. See F. encliandra subsp. microphylloides, one of six subspecies, as well as F. microphylla, which are all in ➤ Section Encliandra.

Milcaos de monte – Mountain [potato] pancakes. An edible mushroom found growing on the trunks of the native chilco (F. magellanica) in southern Chile. Milcaos, the potato pancakes after which the mushroom is named, are a speciality of the island of Chiloé.

Miller, Philip (1691-1771) – Miller, born in Scotland, was the head gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden from 1722 to just before his death. Miller corresponded with many botanists and received plants from all over the world. His knowledge of cultivation was considered unsurpassed during his time—admirers dubbed him the Hortulanorum princeps—and his influence on the botanic world was wide.

Miller, Philip (1691-1771) – Miller, born in Scotland, was the head gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden from 1722 to just before his death. Miller corresponded with many botanists and received plants from all over the world. His knowledge of cultivation was considered unsurpassed during his time—admirers dubbed him the Hortulanorum princeps—and his influence on the botanic world was wide.

About 1730, he received the seeds of a fuchsia shipped from "Carthagena in New Spain" (Cartagena de Indias is on the Caribbean coast of Colombia and was then the capital of New Granada, not New Spain) from fellow Scotsman and botanist William Houstoun (see also). This fuchsia was apparently successfully grown for a number of years before disappearing from cultivation at some point. Since Miller was head gardener from 1722 to 1771, it's unclear at what date the fuchsia was lost. Unfortunately, no preserved specimen of the plant has survived, if any was ever taken.

Said to have been F. triphylla, this identification seems somewhat problematic as that plant is native to Hispaniola while Houstoun was known to have collected instead in areas inland from Cartagena, in modern Venezuela and Colombia. It's quite possible that Houstoun's collection might actually have been of another species in Section Fuchsia, such as F. nigricans, or perhaps F. gehrigeri, and even F. venusta, all common and native to the regions where Houstoun actually collected. Reference to Charles Plumier's Nova Plantarum Americanum Genera would certainly have been where identification of the Houston fuchsia originated. Plumier was considered a very able draftsman by his contemporaries but the somewhat blunt rendition of single F. triphylla blossoms in his book, especially without any foliage, leaves a bit to be desired.

Said to have been F. triphylla, this identification seems somewhat problematic as that plant is native to Hispaniola while Houstoun was known to have collected instead in areas inland from Cartagena, in modern Venezuela and Colombia. It's quite possible that Houstoun's collection might actually have been of another species in Section Fuchsia, such as F. nigricans, or perhaps F. gehrigeri, and even F. venusta, all common and native to the regions where Houstoun actually collected. Reference to Charles Plumier's Nova Plantarum Americanum Genera would certainly have been where identification of the Houston fuchsia originated. Plumier was considered a very able draftsman by his contemporaries but the somewhat blunt rendition of single F. triphylla blossoms in his book, especially without any foliage, leaves a bit to be desired.

Along with F. verrucosa, the four other allied species are vaguely similar to F. triphylla and sympatric to the Venezuelan Andes. They also form a range of naturally occurring hybrids that might confuse casual identification. The plant grown from Houston's collection of seed, probably in modern Colombia or Venezuela, might have been confused with Plumier's original species from Hispaniola and not recognized as something new and different at the time. It's unknown if Miller had a copy of Plumier but Sir Hans Sloan (see also), the great patron of the Chelsea Physic Garden, certainly did. It's also not inconceivable that Houstoun, botanizing in the Caribbean as he did, carried Plumier along or maybe just referred to his memory of the description, and sent the seeds to England already associating them with F. triphylla in some way.

Along with F. verrucosa, the four other allied species are vaguely similar to F. triphylla and sympatric to the Venezuelan Andes. They also form a range of naturally occurring hybrids that might confuse casual identification. The plant grown from Houston's collection of seed, probably in modern Colombia or Venezuela, might have been confused with Plumier's original species from Hispaniola and not recognized as something new and different at the time. It's unknown if Miller had a copy of Plumier but Sir Hans Sloan (see also), the great patron of the Chelsea Physic Garden, certainly did. It's also not inconceivable that Houstoun, botanizing in the Caribbean as he did, carried Plumier along or maybe just referred to his memory of the description, and sent the seeds to England already associating them with F. triphylla in some way.

However, it's still quite possible that the seeds Houstoun sent to Miller from Cartagena de Indias were indeed the real F. triphylla. Several decades later in 1799, passing through Santiago de Cuba on his way to Haiti, the French doctor and botanist Michel-Étienne Descourtilz reported F. triphylla being cultivated at several locations in that city. Later, in volume two of his eight-volume Flore pittoresque et médicale des Antilles released in 1826, he includes an entry on F. triphylla, called the Fuchsie à grappes, in which he goes into some detail on its cultivation and sweet fruit, and its native uses as a dye and medicine.

However, it's still quite possible that the seeds Houstoun sent to Miller from Cartagena de Indias were indeed the real F. triphylla. Several decades later in 1799, passing through Santiago de Cuba on his way to Haiti, the French doctor and botanist Michel-Étienne Descourtilz reported F. triphylla being cultivated at several locations in that city. Later, in volume two of his eight-volume Flore pittoresque et médicale des Antilles released in 1826, he includes an entry on F. triphylla, called the Fuchsie à grappes, in which he goes into some detail on its cultivation and sweet fruit, and its native uses as a dye and medicine.

While the Frenchman draws on his knowledge of F. triphylla from Haiti, the fact he also observed it being cultivated in Santiago de Cuba might lead to the reasonable suspicion that it could just as well have found its way to other major Spanish cities around the Caribbean, such as Cartagena de Indias, already in Houstoun's time. Especially if there were economic, medicinal or culinary uses for the species. Or even if it was just an attractive garden flower.

The mystery remains to be solved.

Miller's author abbreviation in botanical publications is Mill. Also note that his first name is spelt with a single "l".

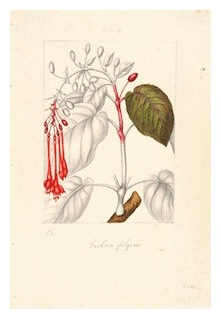

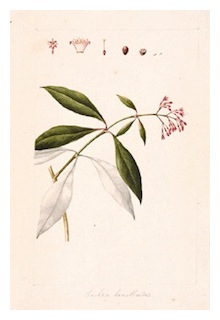

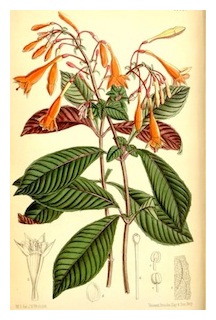

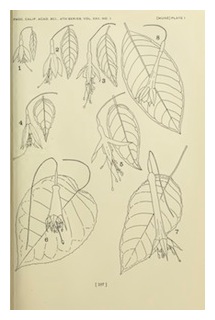

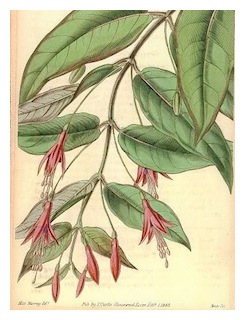

(Illustrations: Compare Plumier's F. triphylla with later botanical drawings of F. nigricans and F. triphylla. Also, the Fuchsie à grappes from Vol. 2 of Michel-Étienne Descourtilz's Flore pittoresque et médicale des Antilles released in 1826. The drawing is by his son, Jean-Théodore Descourtilz, who undertook his own trip to Haiti in 1821.)

Mimo – Very occasionally met as an alternative descriptive name for the fuchsia in Brazil. Depending on the context it can be translated into English as a gift, delight, tenderness or kindness. It's more usually used for a few other plants, such as the Mimo-de-vénus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis or H. mutabilis). See also ➤ Brinco-de-princessa.

Miniata – Red colored. F. miniata (Planch. & Linden 1852) is now a synonym of F. hirtella (Kunth 1823).

Minimiflora – Having tiny flowers. See F. thymifolia subsp. minimiflora in ➤ Section Encliandra.

Minutiflora – Having minute or very small flowers. F. minutiflora (Hemsley 1878) is a synonym of F. microphylla (Kunth 1823). F. minutiflora var. hidalgensis (Munz 1943) is a synonym of F. microphylla subsp. hidalgensis (Munz) Breedlove 1969) as well.

Missouri Botanical Garden – Founded in 1859, the 79-acre Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the oldest botanical institutions in the United States. It's sometimes known as Shaw's Garden after its founder Henry Shaw, a botanist and philanthropist. Along with the public gardens, it includes one of the world's most respected research institutions and herbariums and publishes the Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, a major peer-reviewed journal of botany established in 1914, quarterly. ➤ The Plant List is an new encyclopedic project created the Missouri Botanical Garden and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew to compile a comprehensive list of botanical nomenclature on the internet. It now has over a million scientific plant names of species rank, of which almost 300,000 are accepted species names. See ➤ MBG Website.

Misspellings – See Fuchsia (Misspellings).

Mixta – Mixed. F. mixta (Hemsley 1878) is a synonym of F. microphylla (Kunth 1823).

Monogynia – The classification order of plants with flowers having a single style. See ➤ Octandria Monogynia.

Monospecific – Said of a genus that contains only one species.

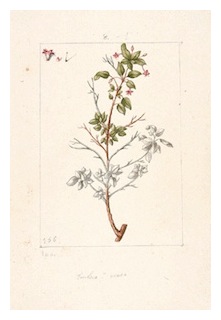

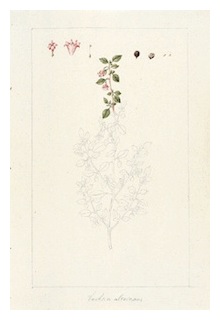

Mociño (Moziño), José Mariano (1757-1820) – Born to a working-class family in Temascaltepec, in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (now in Mexico State in modern Mexico), Mociño's story (he himself almost always spellt his own name Moziño) is one of great accomplishment but also one of bitter disappointment.

Mociño (Moziño), José Mariano (1757-1820) – Born to a working-class family in Temascaltepec, in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (now in Mexico State in modern Mexico), Mociño's story (he himself almost always spellt his own name Moziño) is one of great accomplishment but also one of bitter disappointment.

Mociño studied theology, philosophy and history on a scholarship at the Seminario Tridentino de México, where he graduated in 1778, before turning to medicine, the natural sciences and botany at the University of Mexico in 1784. In early 1790, he was asked to join the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain which had started in 1787 and was organized and directed by Martín de Sessé y Lacosta, a capable Spanish military physician and botanist working from the new Royal Botanical Garden in New Spain, who had secured royal support and funding for the project from Madrid under the reformist policies of Charles III. The highly ambitious aims of the Expedition were to study the natural resources of the vast and mostly uncatalogued territories of New Spain, and study and implement new policies in colonial health and education. One of the hallmarks of the botanical journeys was also a sharp focus on new plants rather than on ones already known.

For his part, Mociño energetically explored in western Mexico (1790-91), along the coast of California and Nootka Island (1792-93), and in Central America (1795-99). While Sessé & Mociño are often accorded joint credit on many of the discoveries, Mociño proved himself to be such a capable and exceptional botanist that his work on the Expedition was to be more of a partnership with Sessé than anything else. It was Sessé who provided able administration and coordination of the explorations but it was Mociño who often provided the botanical scholarship and scientific enthusiasm. In fact, many of the botanical records and manuscripts are entirely in Mociño's hand.

For his part, Mociño energetically explored in western Mexico (1790-91), along the coast of California and Nootka Island (1792-93), and in Central America (1795-99). While Sessé & Mociño are often accorded joint credit on many of the discoveries, Mociño proved himself to be such a capable and exceptional botanist that his work on the Expedition was to be more of a partnership with Sessé than anything else. It was Sessé who provided able administration and coordination of the explorations but it was Mociño who often provided the botanical scholarship and scientific enthusiasm. In fact, many of the botanical records and manuscripts are entirely in Mociño's hand.

By 1803 the project drew to a close and Sessé, accompanied by Mociño, journeyed to Madrid with their specimens, manuscripts and drawings. There they met with political instability and disappointing royal disinterest from an apathetic new monarch Charles IV, who showed no bent for the promotion of science, research and education that had occurred under his father, Charles III. Mociño and Sessé were not able to secure support for the publication of their work and the project languished. Living with Sessé, whose family had some resources in Spain, Mociño managed to get a teaching appointment at the Royal Academy of Medicine in Madrid and served at its president for four years.

Sessé died in 1808 and Mociño, far from his own home and without significant personal or family means, lived under strained circumstances but continued to work on the material and hope for the publication of a Florae. Despite Sessé's death, his situation that year actually looked more promising under Joseph Bonaparte, who had taken over the Spanish throne during the Napoleanic French occupation, as he was appointed director of the Royal Museum of Natural History.

When the Spanish Bourbon dynasty returned to power in 1812 Mociño was forced to flee to France, in declining health and already having been jailed once, because of his sympathies to the Napoleonic cause. Many of the Expedition's invaluable manuscripts and collections would become dispersed between various locations and owners without the oversight of their dedicated trustee. Mociño did, however, manage to bring the botanical manuscripts on which he had himself continued working, as well as the Expedition's valuable illustrations, into exile with him apparently by cart with much effort and struggle. The fine drawings had been prepared in the field with exceptional care by a number capable artists employed by Sessé for the purpose.